Why Cities Need to Prepare for Climate Migration

In October 2017, weeks after Hurricane Maria’s winds peeled Dachiramarie Vila’s wood and zinc house off its foundation, the water and food she had stored began to run out. Supermarkets in her hometown of Las Piedras, Puerto Rico, started rationing goods. Gasoline became scarce. Clean drinking water was hard to come by.

Soon, mosquito bites would dot her children’s bodies. Then Vila’s son fell ill, most likely with an infection from contaminated water. The boy’s pediatrician told her he couldn’t conduct any tests to verify; the laboratory had been destroyed in the storm. That’s when, sitting with the doctor in an unlit hospital corridor, flashlight in hand, Vila broke down.

“I’m going,” she said she later told her family. “I can’t do anything else. I can’t live like this anymore.” Vila, her husband, and their two children—along with eight extended family members—fled to Orlando, Florida.

People reach out to receive supplies after a warehouse with supplies believed to have been from when Hurricane Maria struck the island in 2017 was broken into in Ponce, Puerto Rico on January 18, 2020, after a powerful earthquake hit the island. President Donald Trump on January 16 freed up emergency aid for Puerto Rico's recovery from a January 7 earthquake that caused widespread disruption and damage on the island. Trump's declaration of a major disaster in Puerto Rico makes federal funding available for repairs, temporary housing and low-cost loans "to help individuals and business owners recover from the effects of the disaster," the White House said. (Photo by RICARDO ARDUENGO/AFP via Getty Images)

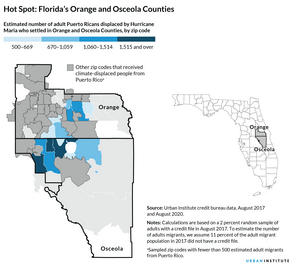

With that decision, they became among an estimated 135,592 people to evacuate Puerto Rico for the mainland in the six months after Hurricane Maria pummeled the island.

For Orlando and its surrounding counties, the influx of people from Puerto Rico served as a crash course in emergency coordination and collaboration. Longer term, the city also had to adapt to the resulting population shifts, which added demand for housing when available and affordable stock was already limited. The housing crisis continues here—and in Florida—mirroring the reality across the US today, where less housing is available for sale or rent than at any time in the past 30 years.

“This is not a matter of if it’s going to happen in your community, it’s when it’s going to happen.”

Orlando isn’t the only city receiving climate migrants displaced by weather-related disasters and the chronic effects of climate change. After Hurricane Maria, an estimated 56,477 Puerto Ricans relocated to Florida, but the next-largest shares of evacuees landed in Massachusetts and Connecticut. Experts anticipate climate migration will increase (PDF), particularly from the US Gulf Coast, sections of the Atlantic Seaboard, and other geographies vulnerable to extreme climate change effects. They stress that communities need to prepare to integrate climate-displaced families for short or cyclical periods, or permanently.

“This is not a matter of if it’s going to happen in your community, it’s when it’s going to happen,” said Fernando Rivera, professor of sociology and director of the Puerto Rico Research Hub at Orlando’s University of Central Florida (UCF). “I don’t think anybody could safely say, ‘We will never be affected by these issues.’”

Effects of climate migration expected to be widespread

Flash flooding in Tennessee. Wildfires in California. Water shortages in the Colorado River basin. Tornadoes through nine midwestern and southern states. These 2021 events, many of them made worse by certain development practices and human-induced climate change, threatened the stability of communities and homes, propelling some people to resettle elsewhere.

Depending on a disaster’s severity and geographic range of damages, whole communities or even counties can be displaced. Though migration is difficult to predict with certainty, some models project that tens of millions of Americans will be forced to move away from their homes because of wildfires, submerging coastlines, and other climate-related threats.

Oftentimes, climate-displaced people move multiple times. “There’s a first evacuation, then they may move from a hotel or a family’s house or a temporary shelter to another place—another apartment, another house,” said Carlos Martín, a David M. Rubenstein Fellow at the Brookings Institution and climate mitigation and adaptation expert.

Generally, movement among Puerto Ricans has for decades been “circular,” UCF’s Rivera said, meaning that many live for periods of time between the island and states like Florida and New York. This cyclic pattern can be spurred by various factors, including environmental conditions and economic crises, such as when the US territory declared bankruptcy just months before Hurricane Maria hit.

“All those types of things tie up to people saying, ‘Look, you know what, I’ve had enough,’” Rivera said. “And I think Hurricane Maria just accelerated the migration of Puerto Ricans.”

People can be drawn back to the island for diverse reasons too, including how they are received on the mainland; the island can provide cultural familiarity and serve as a refuge from the sting of discrimination and frustration of language barriers some Puerto Ricans may experience on the mainland, Rivera said.

Receiving communities, the places where climate-displaced people relocate, can benefit from the economic, social, and cultural contributions new residents bring. Communities can also face their own challenges as they welcome folks: all regions in the US are experiencing a lack of affordable housing, which worsens when natural disasters destroy housing stock in one place and increase demand in other places when residents move. Existing housing providers, as well as financial and health services, can become overwhelmed and may not be prepared to address displaced people’s specific needs. Long-term residents may also perceive newcomers as competitors for jobs and housing—especially where there was already a shortage.

Across the country, however, few policies and programs have been established to help communities prepare for or respond to the systemic shocks climate migration can bring. And though most people are familiar with national and international response efforts of organizations such as the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and the Red Cross, less is known about the capacity of states and localities to respond to displaced people’s needs. Research on disaster-influenced migration is also limited, focusing primarily on who moves following a climate event. And little is known about what happens to displaced people like Vila and her family after they relocate.

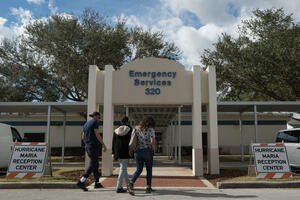

People get information at the Reception Center for Puerto Rican refugees set up at the Orlando International Airport in Orlando, Florida on November 30, 2017. On September 20 powerful Maria tore across Puerto Rico, destroying homes, shattering the island's rickety power grid and phone network, and leaving its 3.4 million residents in the dark and incommunicado. Since the hurricane struck at least 212,000 people have traveled from Puerto Rico to Florida -- mainly central Florida, according to figures from the State Emergency Response Team (SERT). (RICARDO ARDUENGO/AFP via Getty Images)

How Orlando agencies collaborated to support climate-displaced people

Three days after Hurricane Maria’s September 20 landfall in Puerto Rico, Orlando’s Heart of Florida United Way convened upward of 65 government, nonprofit, and business leaders from the city and Orange, Osceola, and Seminole Counties to prepare for evacuees.

Initially, “no one knew what we were doing at all,” said Delitza Fernández, project manager at Heart of Florida United Way, which supports health and human services agencies in Central Florida.

Given the tricounty area’s large Latino population, as well as its historic role as a landing point for Puerto Ricans coming to the mainland, leaders were confident many Puerto Ricans would evacuate to the region.

People get information at the Reception Center for Puerto Rican refugees set up at the Orlando International Airport in Orlando, Florida on November 30, 2017. On September 20 powerful Maria tore across Puerto Rico, destroying homes, shattering the island's rickety power grid and phone network, and leaving its 3.4 million residents in the dark and incommunicado. Since the hurricane struck at least 212,000 people have traveled from Puerto Rico to Florida -- mainly central Florida, according to figures from the State Emergency Response Team (SERT). (RICARDO ARDUENGO/AFP via Getty Images)

By early October, Florida’s then-governor Rick Scott established disaster relief centers at the Orlando International Airport, the Port of Miami, and Miami International Airport to provide immediate connections to local and state resources to people arriving from Puerto Rico.

As evacuees deplaned in Orlando—many of them elderly, and some who had never left their island home, according to advocates—they were greeted by an airport or airline official and directed to a reception center at the far east end of Terminal A. The area was staffed with representatives from local and state agencies and charitable organizations who connected Puerto Ricans to emergency shelter, FEMA financial assistance, job referrals, clothing and food assistance, school registrations and health services, and other community resources.

Given the emergency, many institutions adjusted procedural requirements to allow incoming migrants to receive state services, such as obtaining driver’s licenses and other identification on site at the welcome center. Florida, like many states at the time, also allowed student evacuees to qualify for in-state tuition so they could continue their education.

Working professionals received support too. The state’s division of emergency management helped expedite licensure transfers for nurses, doctors, engineers, and other professionals “so they could get to work right away,” according to David Barnett, human services manager for Osceola County, who had a team at the airport reception center.

The center remained open until December 2017. The following month, officials launched the Multi-Agency Resource Center in a vacant building near the airport and continued providing services until March 2018.

Finding temporary and permanent housing for evacuees was daunting. Typically, disaster survivors displaced from their homes receive FEMA financial assistance for temporary shelter. That initial support period can cover the cost of a hotel room or similar accommodation for 5 to 14 days and may be extended in 14-day intervals for up to six months from the date of the disaster.

In the Orlando and Kissimmee area, FEMA provided multiple extensions on housing vouchers “until they couldn’t extend anymore, and some of those families entered in the street,” said Ana Cruz, coordinator of the city of Orlando’s Hispanic Office for Local Assistance (HOLA). “The families who had a place to stay or the ones who found housing right away, they were the lucky ones.”

Cruz contends that affordable housing challenges were a critical factor for many families who decided to return to Puerto Rico, move to a different region of Florida, or relocate out of state.

Indeed, even before the influx of people after Hurricane Maria, the Orlando region lacked affordable housing options. Today, almost 58 percent of Orange and Osceola County residents pay more than 30 percent of their income for housing, according to the Orlando Business Journal. And more than 27 percent are using more than half of their wages to pay rent or a mortgage. Meanwhile, the Orlando region remains an attractive destination, with more than 1,500 people expected to move to the area every week over the next eight years—which could further squeeze the housing market.

“Right now is one of the most difficult times we’ve had in terms of helping people get into housing,” said Osceola County’s Barnett, who oversees housing and other social service programs in the county. Many local hotels near Walt Disney World “have become, by default, our affordable housing places” until people can transition to more stable housing.

While area cities, counties, churches, and nonprofit organizations contributed to helping people secure housing, from the onset, Heart of Florida United Way took the lead on the task. Temporary shelters filled up two days after the welcome center opened, Fernández recalled, so United Way began housing evacuees at airport hotels, then eventually at hotels across Orlando and in neighboring counties.

The nonprofit paid discounted rates it negotiated with the hotels and ultimately purchased more than 3,000 hotel nights that provided nearly 1,050 people with emergency housing assistance. Costs were largely covered through unrestricted support from Orange County government, as well as major private-sector donors, including Publix, Walt Disney World, and Duke Energy, Fernández said.

Elsewhere, landlords offered space at reduced rates, though some also raised their rents because of increased demand. Residents opened their homes. Support came from afar too; people from other Florida cities and other states called Cruz to inform her of available housing and jobs.

“Looking back, one of the incredible benefits that came from this was just the collaboration that came out of us trying to service people who were coming here to seek safety,” said Chris Castro, director of sustainability for the City of Orlando. “Hotel rooms really became housing for a lot of the people who came here.… We were fortunate that many of those were opened up to families at low or no cost and allowed them temporarily to get their footing and figure out what their next step was going to be.”

It was in one of the Orlando area’s hotels where Vila’s entire family eventually found shelter too.

A climate-displaced family struggles to find stable housing

About five weeks after the hurricane, Vila arrived in Orlando with one suitcase for her immediate family.

“The whole flight I was crying. It was shocking for us and very traumatic,” she said. When she deplaned, it was as if she had landed on another planet: There was light. People drinking soda with ice in it. Others on vacation, sporting Mickey Mouse t-shirts. “And we are crying. My children, full of mosquito bites.”

“What they did tell us is there was no housing. From the beginning, they said, ‘There is no good housing, we are full.’”

Shuttled to the reception center, Vila remembers feeling numb as she bounced from table to table, collecting this brochure, that flyer, digesting information. “Really, the only organization that was hand in hand with us was HOLA.… We arrived lost and they were the only organization that guided us,” Vila said.

“What they did tell us is there was no housing. From the beginning, they said, ‘There is no good housing, we are full.’”

Her entire family initially stayed for three nights at a Kissimmee hotel Vila’s sister-in-law had once booked for a visit to Walt Disney World. They had nowhere to stay by the fourth morning; the hotel was full. So, that day, Vila and her family walked for hours along the east-west artery of US Route 192, popping in and out of the hotels that dot it, searching for shelter. They eventually found it at one hotel, and later, at another.

All the while, Vila’s mother hunted for something more stable. After two weeks of bouncing between hotels, she qualified for a two-bedroom apartment through her and her husband’s Social Security benefits. All 12 family members squeezed into the apartment.

It’s been four years now, and that apartment is where Vila and her husband, Luis, their 15-year-old son of the same name, and their 8-year-old daughter, Saymaris, call home. Vila’s sister and her family returned to Puerto Rico a month after arriving. Her parents and brother lived with Vila for one year, returning home only after her parents were able to fix up their house.

Today, Luis is the maintenance manager at the apartment complex in which they live. Vila is a school clerk at an Orlando elementary school, earning $10 an hour. Her children, now in 2nd and 10th grade, are thriving.

“We would like to stay here if possible,” Vila said, “if things improve and we can manage to have a home of our own.”

Puerto Rican residents of the Super 8 motel in Kissimmee, Fla., on Wednesday, May 16, 2018. A federal judge has extended the temporary federal hotel voucher program housing Hurricane Maria evacuees on the mainland until August 31. (Ricardo Ramirez Buxeda/Orlando Sentinel/Tribune News Service via Getty Images)

Steps cities can take to prepare for climate-displaced people

Orlando’s experience offers lessons for other cities. Castro, Orlando’s sustainability director, said city leaders are increasingly thinking about how to plan for challenges related to housing, food insecurity, jobs, and education as climate migration becomes “a more prominent issue later into this century.”

“Begin to build the governance and the capacity around resilience to [climate migration] so that when it does come, you already have an entity… that is working together to advance progressive policy or programs or investments that are strategic.”

The population influx during the 2017 hurricane season not only amplified the pressure on the area’s affordable housing supply; it also “bolstered the fact that we needed to enable [access to] more housing stock to our community in creative ways, not just your traditional certified affordable housing development,” Castro said.

One solution the city advanced a year after Hurricane Maria was to allow residents in all neighborhoods to build accessory dwelling units on their properties to help alleviate the affordable housing shortage and get “ahead of migration.” Castro and others in the Orlando area suggested that every community across the country should start preparing now for the possibility—or in some locations, the inevitability—of becoming a receiving community for climate migrants.

“Begin to build the governance and the capacity around resilience to [climate migration] so that when it does come, you already have an entity… that is working together to advance progressive policy or programs or investments that are strategic,” Castro said. Orlando, for instance, helped establish the East Central Florida Regional Resilience Collaborative to coordinate climate mitigation and adaptation efforts with other cities.

Martín, of the Brookings Institution, suggested that communities will want to think about future growth, whether or not people arrive for climate-related reasons. For instance, the Orlando area grew by 2.4 percent to just above 2.5 million people from 2018 to 2019—primarily because of people moving to the area. By 2030, the population is expected to reach 5.2 million. “Some of that growth is going to be coming from outside, from people who don’t look like you, who don’t have the same means as your current community might have,” Martín said. “So, what sort of services are you preparing for them as well?”

That includes planning for a mix of housing options for more people than otherwise expected in some areas, including adjusting land-use and permitting guidelines and allowing for and incentivizing development of rental stock and high-density housing, such as duplexes and triplexes concentrated in quality neighborhoods.

UCF’s Rivera and United Way’s Fernández stressed the importance of city leaders expanding their cultural competency. By understanding more about the diversity of people in their communities, cities can better anticipate and respond to the needs of newcomers from other regions of the US, including climate-displaced families.

And Vila recommends that every city establish a culturally competent place like HOLA that works directly with community members. A place that provides a personal touch, she said, as it connects people to resources to help them meet their basic needs and more.

“I would like the experience that I had [to serve others], that my voice reaches out to people who have more power, and people who can influence, so that when the situation arrives, it works well,” Vila said.

“I tell people, get ready.”

Forthcoming research

Urban Institute experts are investigating the effects of climate migration on receiving communities and people displaced because of weather-related events. Forthcoming findings from our study of three Gulf Coast regions, including Orlando and surrounding Orange and Osceola Counties, will provide insights to help communities prepare for and adapt to climate migration and effectively respond to the needs of climate-displaced people.