For Owners and Renters, Home Modification Assistance can be a Lifeline

by Maya Brennan

Are there any steps? How wide are the doorways? Any narrow corners to navigate? How high are the counters and light switches? Searching for an accessible home to buy or rent can be like looking for a needle in a haystack, but it’s something that a growing number of people need to do.

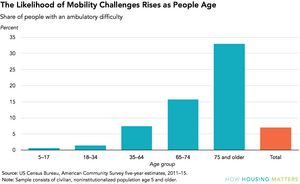

The ease of movement that many people take for granted is far from universal. Around 1 out of every 14 people in the United States has mobility challenges. The likelihood of mobility impairments rises to 1 in 6 among people ages 65 to 74, and then 1 in 3 among people ages 75 and older. Already, more than 17 million US households include a person with a mobility impairment. With an expected doubling of the senior population by 2060, more homes will need to be accessible to ensure disabled residents’ independence and to accommodate mobility-impaired visitors.

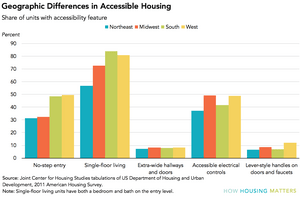

Though some accessibility features are required in new multifamily stock, much of the nation’s housing is either exempt or was built before the guidelines took effect. As a result, the country has a shortage of accessible homes. Although single-floor living options and no-step entry are more common in the South and West (perhaps because of the relative age of the housing stock), no region has a sufficient stock of accessible homes. According to a HUD report, less than a fifth of a percent of housing units nationwide are wheelchair accessible. This may explain why the majority of disabled households live in a home that does not meet basic accessibility standards.

The onset of mobility problems leads to a choice between moving, making do (e.g., relying on other household members for help), or modifying the home. But can owners and renters who need home modifications afford the cost?

Home modifications may be out of range for cost-burdened renters and owners

Though not often considered to be in the market for home improvements, renters with disabilities typically bear the cost of any accessibility modifications. Though the Fair Housing Act requires landlords to allow reasonable accommodations for disability, under most circumstances they have no obligation to pay for changes to an apartment or to a building’s common areas.

The property owner is responsible for the costs only if accessibility was already legally required, such as in certain multifamily properties covered under the Fair Housing Act or in public spaces covered by the Americans with Disabilities Act, such as public housing, a homeless shelter, or a property’s leasing office. Relatively few rental properties fit within these exceptions, so renters usually need to pay for the modifications. They may also bear the cost of restoring the property to its original state if the changes are likely to affect the unit’s appeal to future residents.

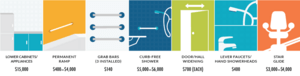

The costs can quickly add up. Considering the state of the housing stock, the typical home is likely to need a ramp ($400–4,000, depending on the size and configuration), wider hallways and doors ($700 each), and different faucets and showerheads ($400), among other changes. The total price can easily run into the thousands of dollars.

And that is more than many older households can afford.

Approximately 4.8 million older households spend more than half their income just to stay housed, and the number of severely cost-burdened seniors is expected to skyrocket, surpassing 8 million by 2035. Paying such a high share of income for housing means less money is available for food, health care, and transportation—and would likely push accessibility features out of the budget.

Severe housing cost burdens aren’t just a problem for renters. Older owners account for 2.9 million of these severely burdened households, reflecting both their income constraints and the fact that homeowners are increasingly bringing debt with them into the retirement years. This means that millions of homeowners, who tend to buy “Peter Pan” homes (designed for people who never grow old) all the way up to retirement, may face high home modification expenses and little capacity to afford them.

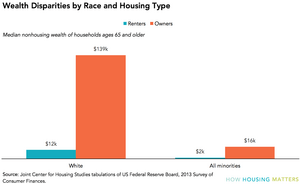

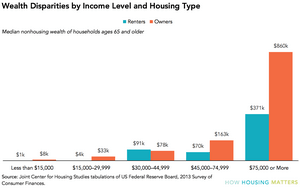

For owners, home equity or other retirement assets may supplement a lack of cash on hand. But the asset portfolio of older renters rarely can. The median wealth of an older renter household is $6,150—well below that of owners. This average, however, obscures serious wealth shortfalls among lower-income renters and racial and ethnic minorities. Older renters living on less than $15,000 per year hold a median of $1,300 in assets, and older minority renters across all income groups hold a median of $1,600 in wealth. Home modification is just one of many aging-related expenses that this nest egg may need to cover.

Solutions from the public, private, and nonprofit sectors

The public, private, and nonprofit sectors can work together to ensure that older or disabled households don’t need to choose between a home they can safely navigate and the resources for other basic needs. The set of solutions includes supporting and expanding existing programs that allow homeowners to afford home modification, using the evidence to build and test new ideas to address renters’ unmet needs, and prioritizing accessibility for the future housing stock.

The growing need for accessible housing calls for federal, state, and local governments to continue and expand supports for older owners. When homeowners need to pay for ramps, chairlifts, or other home modifications, they can draw from home equity or may be eligible for funds through the US Department of Veterans Affairs, Medicaid Home and Community-Based Services waivers in certain states, or other state or local assistance programs.

Programs that support a variety of needs related to aging in place may include supports for home modification. CAPABLE and Bath Housing’s Comfortably Home program are two models that can be replicated in other communities, whether with federal, philanthropic, or other resources.

For renters, the menu of solutions is less established. These might include tax credits, grants, or other incentives for property owners to make common areas or apartments accessible. Financial assistance and grant programs could also be offered directly to low-income renters to help with the cost of modifications and prevent people from staying in a home that is no longer accessible or safe. Impact investments, pilot programs, policy dialogues, and competitions could all contribute to developing and testing these new approaches to serve an urgent and growing problem.

Finally, the population of tomorrow will live in homes that exist or are being built or planned today. Universal design guidelines and incentives would expand the accessible housing stock as new homes come online or undergo substantial rehab. By emphasizing accessibility from the start, the housing stock will eventually need fewer and less costly home modifications so that people with mobility challenges can be independent in their homes and easily welcomed into the homes of family and friends.

Elizabeth Forney, Serena Lei, Brittney Spinner, Jerry Ta, and Daniel Wood of the Urban Institute contributed to this feature.