Nick Lundgren/Shutterstock

In the Twin Cities, Affordable Homeownership Is Increasingly Inaccessible for Black Families

Homeownership is the key way most middle-class Americans build family wealth. And homeownership is especially important for Black families, whose wealth is more closely linked to homeownership than white families. Far more than stocks, bonds, or other investments, home purchasing offers people a place to invest their equity in something permanent, which, in many cases, gains value over time.

But deep structural racism and classism have made access to homeownership inequitably distributed along racial and class lines. Nowhere in the US is this inequity greater than in Minnesota’s Twin Cities, a region encompassing Minneapolis, Saint Paul, and their suburbs, where Black families own homes at less than one-third the rate of white families—the largest gap in the nation.

In new research conducted in partnership with local housing and economic development partners, including the Alliance, the Family Housing Fund, and the Center for Economic Inclusion, we investigated how homeownership patterns have stripped wealth from Black homeowners in recent decades and which neighborhoods have been most affected. We find changes in local and regional policy can reduce homeownership inequities in the Twin Cities, if designed intentionally and implemented effectively.

Historic and current explanations for the homeownership gap

Until the passage of the 1968 US Fair Housing Act, racial discrimination was legal in many places, meaning Black families were frequently denied the ability to buy homes in neighborhoods with high-quality public services. They were often also offered loans at less affordable rates than white families.

The Fair Housing Act ruled such actions illegal. But systemic racism persisted through implicit means, and access to housing today is still inequitable. Black families have less access to generational wealth passed down over the decades—a frequent source of assistance for white families buying homes. Because of these wealth differences, they have lower credit scores. And neighborhoods where Black families live suffer from disproportionately higher property taxes, even as their homes are undervalued.

Together, these conditions impede Black residents’ wealth building and wealth sustenance in many US cities today. And the consequences are dire: in the Twin Cities, 70 percent of white families own their homes, but just 20 percent of Black families do.

The gap is growing, particularly in neighborhoods experiencing gentrification

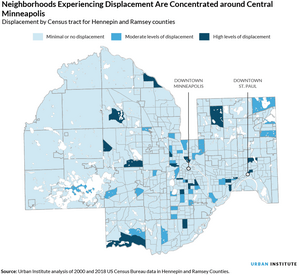

When we compared changes in the two counties at the center of the Twin Cities—Hennepin and Ramsey Counties, which respectively include Minneapolis and Saint Paul—we found the homeownership gap has increased by 10 percentage points since 2000. In other words, inequality has worsened.

This problem is particularly severe in areas experiencing gentrification, where average incomes are rising, new investments are occurring, and residents with low incomes are being displaced. Those neighborhoods, which surround downtown Minneapolis, are experiencing rapidly rising rents, making it more difficult for families with lower incomes to afford living there, ultimately reducing prosperity for the region as a whole (PDF).

Black homeowners are leaving because of increasing property taxes, a sense of cultural displacement, or simply the ability to get a good deal on the homes they currently own. Although 30,000 new Black residents moved to the region between 2000 and 2018, the number of Black homeowners declined in neighborhoods around Central Minneapolis.

In addition to the shrinking Black homeowner population, institutional investors have purchased an increasing share of local single-family homes and have converted them to rentals. We identified this phenomenon in communities like North Minneapolis and central sections of Saint Paul, where, in many cases, investors purchased homes foreclosed upon during the Great Recession—a time when many Black families lost their homes.

In North Minneapolis, investors own and rent out more than 10 percent of housing. They impede the potential for wealth building through homeownership by limiting the number of affordable homes and replacing them with rental units. In some cases, these units are more expensive to rent monthly than they would have been for families to own, if they had been able to buy them. Research on other cities shows these types of investors compete for home purchases and are more likely to evict tenants (PDF), exacerbating the challenges of finding affordable, stable housing

Opportunities to address the roots of the problem

The inequities Black families experience in the Twin Cities illustrates the larger systemic barriers surrounding race and opportunity in the United States. But changes in policy and practice can encourage better outcomes, despite the magnitude of this problem. Through our work with local partners in the Twin Cities, we’ve identified several actions policymakers at the city, county, and state governmental levels can consider as they collaborate with advocates and community members to build opportunities for more equitable access to homeownership, as they shore up the rental housing situation to offer alternatives where buying a home isn’t possible:

- Allocate additional local and state funding for homeownership counseling to aid families of color in their search for good financing options for new home purchases and to prevent existing homeowners from being foreclosed upon.

- Increase down payment assistance support for families with low incomes, with an emphasis on Black families who already live in, or are interested in purchasing a home in, gentrifying neighborhoods.

- Dedicate new city, county, and state funding to build and renovate affordable rental housing (PDF) for families with low and moderate incomes.

- Stabilize rent in neighborhoods that have been particularly vulnerable to gentrification.

- Strengthen anti eviction laws, building upon progress by the State of Minnesota and cities like Minneapolis that’s made it more difficult to evict people from their homes without just cause.

Together, these policies are an important step forward in building equitable access to homeownership and affordable rental housing throughout the Twin Cities and other rapidly changing regions.

This post originally appeared on Urban Wire, the blog of the Urban Institute.