Young and Homeless in Washington, DC

Writing by Serena Lei and photography by Maura Friedman

In late August, fall classes at Trinity Washington University had just begun, but Bre* was already thinking ahead to winter break. When the semester ends and the dorms close, she will be homeless again.

The possibility that she would have to go back to the women’s shelter is weighing on her. Her first stay there last year left her rattled. Bright, resilient, and motivated, Bre’s not easily rattled. Even when she and her boyfriend were sleeping in a tent under the Third Street Tunnel, she kept her spirits up by pretending they were camping. When she was living out of an abandoned DC house with no water or electricity, she still showed up for work at her retail job in Maryland. But the shelter made her feel unsafe and anxious, like she was losing her mind, seeing in some of the older women a long-term homelessness she feared.

“You had people in the shelter for years and they’re comfortable with it,” Bre, 24, said. “It can break you, seriously. I’m not going to say I was broken, but when I felt myself getting a tad comfortable, I was, like, no. Got to get on my feet. This isn’t going to be me.”

She’s not alone in her reluctance to stay in a shelter. Many youth experiencing homelessness report avoiding shelters because they don’t feel safe there or can’t relate to the older adults, but they often don’t have another option.

It’s a problem that many jurisdictions are working to correct, understanding that although homeless youth and homeless adults have similar needs, reaching these young people may require different spaces and different strategies.

Ending homelessness in the nation’s capital

In 2015, DC released a five-year plan to prevent and end homelessness among single adults and families. Kristy Greenwalt, director of the DC Interagency Council on Homelessness, said that they didn’t have enough data about homelessness among DC youth to include them in the first strategic plan. Instead, planners initiated an annual youth census called DC Youth Count and began developing a coordinated entry system to connect the efforts of service providers across the city.

The latest census, in 2017, counted 1,117 unaccompanied youth and youth heads of households experiencing literal homelessness or doubled up with friends or strangers. But homeless youth are difficult to count, and official estimates are widely considered undercounts. Youth often hide their homelessness and aren’t connected to social services and formal supports.

“Do I tell people I’m homeless? No. And I do my damndest not to look like it,” said King, 25, who has been homeless in DC for roughly three years. “People change their perception of you.… It’s like, they feel like you’re dirty or have bed bugs.… Just because someone’s homeless doesn’t mean they’re addicted to something or that they chose to do drugs. Or it don’t mean that they don’t know how to live life. Some people fall down sometimes and they need some help getting back up.”

Like many others, Bre keeps her situation to herself, telling only a few people that she’s homeless. She’s not ashamed, she said, but she doesn’t want people to treat her differently or think she wants a handout.

Greenwalt said the census also sheds light on the challenges many face. “Through the data work we did around the youth census, people have come to understand just how vulnerable these young people are, how much trauma they’ve had in their early lives…mental health, family neglect and abuse, sex trafficking,” Greenwalt said. “All those things inform the service model and approach we need to use.”

In 2017, the city launched a separate plan for youth younger than 25, with the goal of preventing homelessness or ensuring that it is a “rare, brief, and one-time experience.” Helping youth find stable footing and helping them get on a different path could prevent years of chronic homelessness.

Greenwalt is optimistic but cautious about the progress DC has made. Systems change is difficult and slow. And homelessness is just the most visible piece of a deep housing crisis where too many struggle to pay rent or stave off eviction.

“People are engaged in a way that I don’t think has ever happened before,” Greenwalt said. “The optimistic side of me feels like mayors and governors are now seeing that we are in a state of crisis. We certainly could use more federal resources, but a lot of the solutions around housing are local solutions.… We know a lot about what it takes to end homelessness.… The solutions are quite clear. What’s hard is how you actually implement [them].”

Drop-in centers: A first step on the path to stable housing

At 10 a.m. on a Thursday morning, about 15 people have gathered in the living room of Sasha Bruce Youthwork’s drop-in center. It’s a daily tradition at the center for clients and staff to check in and talk about their goals for the day, whether it’s getting an ID, filling out job applications, or just having a good shift at work.

Drop-in centers like Sasha Bruce’s in Barracks Row and Latin American Youth Center’s in Columbia Heights are frontline services for homeless youth. They’re a home base, providing access to meals, a kitchen, showers, washing machines, and computers. Research suggests that drop-in centers can be a critical first step toward long-term goals, like finding permanent housing. As a low-barrier program with no prerequisites, these centers are a valued entry point for disconnected youth and help build trust between youth and service providers.

“Even if we never get anybody to get their GED or their ID or a job, if we can provide them one strong, healthy, positive relationship that they can go back to when they need some guidance or support, that matters,” said Pam Lieber, program manager for Sasha Bruce’s youth drop-in center. “While you’re here, I can do everything I can to let you know that you’re worthy and you’re loved and you’re valued and matter.”

Lieber, who has been working with homeless youth for some 20 years, is enthusiastic about the way DC’s strategic plan has improved collaboration, getting stakeholders and service providers on the same page to create a coordinated system.

This summer, Sasha Bruce’s drop-in center averaged 40 to 50 young people a day. Youth line up outside before 7 a.m., often coming from shelters or transitional living programs that close in the morning. The reception from the community has been mixed. Some business owners have hired youth or donated food and resources, but others have complained about the people the drop-in center attracts.

Lieber said that she hears a lot of misconceptions—that youth experiencing homelessness are addicts, that they’re “out there running wild.” But some of the youth who come to Sasha Bruce are homeless because they’ve left parents who are addicts or households that sell drugs. They have a sense of hope, she said, that this is not their permanent state, that they will not be chronically homeless.

Tailoring solutions for youth

In many ways, the strategies to end adult homelessness are the same as for youth: stable housing, supports, and a systems approach that is flexible enough to meet individual needs. But research shows that homeless youth need services tailored to their needs and that support their transition to adulthood. And, as DC’s strategic plan lays out, youth may need help developing healthy relationships with adults, learning how to live independently, and addressing behavioral health conditions that often emerge in young adulthood.

“The program models might be the same,” Greenwalt said. “But because of the unique developmental stage of young people, the interventions definitely look a bit different.”

Take transitional housing. Greenwalt said it’s a model that isn’t used as much now for homeless adults but can be a first step for youth, many of whom have never lived on their own and may need more support and oversight as they transition from homelessness to permanent housing.

“A lot of the problems that the youth in my community have is…this really big gap of education that we miss between 16 and 21 that covers credit, taxes, student loans, financial advice,” King said. “I feel like they’re things…that you would normally ask your parents.”

Youth homelessness also differs from adult homelessness in the role that family and schools play in helping young people get back on their feet. For example, the less engaged homeless youth are in school, the less likely they are to reunite with their families and escape homelessness.

What’s more, different groups may need different interventions. LGBTQ youth, who are overrepresented among homeless youth, have high rates of mental health issues, substance abuse, suicidal behavior, sexual and physical victimization, discrimination, and stigma.

Madeline, 19, chose to leave home because her family did not accept her identity as a transgender woman. The stress made her suicidal, forcing her to drop out of college and leave the music program she loved. Although she’s working toward going back to school, she’s not ready yet. For now, she lives inA a transitional housing program and spends her days at the Latin American Youth Center’s drop-in center practicing violin. Just having a place to stay while she figures out her next step is valuable.

“A common misconception with the youth is that…a lot of us are just lazy and don’t want to work,” Madeline said. “Sometimes you have to get yourself straightened and your mental health straightened [first].”

In DC’s youth census, the most common reason given for homelessness was conflict among family or friends, followed by economic factors, like eviction, job loss, and lack of affordable housing.

Family instability is a major driver of youth homelessness. Young people may be forced to leave their homes or felt that leaving was the only option to escape abuse, neglect, or conflict. When Bre lived with her grandmother, they fought—often. When it got to be too much, Bre left home, feeling like it was her only option.

Sometimes youth may be expected to go out on their own when they turn 18 and their families can’t support them. And many youth end up homeless when they age out of foster care or leave the juvenile justice system.

But it’s not just an individual story. Some researchers argue that the existence of youth homelessness is a sign that our child welfare, safety net, education, and health care systems are failing to protect children and young people. A 2016 study of 676 homeless youths in 11 cities found that more than half had lived in foster or group homes, more than 60 percent had been arrested, and more than two-thirds reported regular interactions with law enforcement.

Nationwide, youth experiencing homelessness are disproportionately African American. In the District, decades of discriminatory policies and practices in housing, employment, criminal justice, and education have stacked the deck against black residents, including black youth, contributing to housing instability and making it more difficult to escape homelessness.

The lack of affordable housing also plays a major role in homelessness. Entry-level jobs often don’t pay enough to afford housing, especially in an expensive city like DC. And the neighborhoods that they can afford might be the ones they’re trying to escape.

“Unless you’re working two to three minimum-wage jobs, you’re not going to be able to afford living in the city. And it sucks, because it’s the only place I’ve ever been,” King said. “I don’t know nowhere else…. At least in DC, I might see a familiar face. I know where the different resources are.”

From the Third Street Tunnel to a college dorm

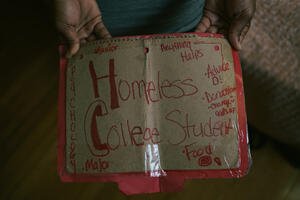

In her dorm room at Trinity, Bre keeps the sign she used when panhandling to remind her of how far she’s come.

Bre has been homeless since 2015 when she left her grandmother’s house. When she didn’t have enough money for food or a Metro ride to work, she stood on street corners with her sign, asking for help.

On February 15, 2016—Bre remembers clearly that it was the day after Valentine’s Day—she was panhandling at North Capitol and K Streets. It had just stopped snowing and the roads were slick. A truck skidded as it turned the corner and slammed into her, pinning her to a light pole. The impact broke her back and her pelvis, though all she knew in that moment was that her body was consumed by pain. As she drifted in and out of consciousness, she heard the truck driver crying.

Bre had seven surgeries after the accident. Her doctor told her it might take a while for her to walk again, which only motivated her to work harder to recover. She was determined to go back to school, to get another job.

“One thing I always tell people, you’ve got to keep going, no matter what,” Bre said. “You have to be optimistic, even in the crazy situations.”

Through months of physical therapy, Bre learned to walk again. In the fall, she was accepted into Trinity and started taking classes the following January. She was still homeless, living in the women’s shelter and then in a transitional living program, until her dean suggested she move on campus.

“It’s been the best decision I’ve made,” Bre said. “When school is actually open, I get full meals. I can come and go as I please.… I have my own room.”

With a stable place to live and study, Bre’s GPA has gone up, and she’s on track to graduate next May. Still, she will need to find a place to live over the monthlong winter break. And she still struggles with trauma from the accident. Sometimes she’ll walk by North Capitol and K Streets, the spot where she was hit, to face the memory and challenge herself to overcome it.

“I’m literally at the end of the tunnel. I’m just trying to get further to that light,” she said. “I don’t care how hard it is. I don’t care how tired I get. If I want something for myself, I’m going to have to go get it. All I have is me, so I’ve got to do what I can.”

* Some of the youth we interviewed requested that we not use their full names, so we applied that practice to each of the young people in this story.

We would like to thank Maya Brennan, Oriya Cohen, Gillian Gaynair, David Hinson, and Jerry Ta for their contributions to this story.