Why Schools Should Care about Housing Voucher Discrimination

What happens in our neighborhoods is reflected in our schools. Inequality in our neighborhoods translates to inequality in our schools. And discrimination that has a hand in shaping our neighborhoods, has a hand in shaping our schools.

About 70 percent of K–12 students attend an assigned school. If housing near higher-performing public schools is unaffordable, then those schools are also out of reach. Housing vouchers help nearly 2.2 million families afford a home and give them a chance to move to better-resourced neighborhoods with better-resourced schools. But landlords hold a lot of power in deciding which neighborhoods families have access to, and research shows many refuse to accept vouchers.

What’s more, voucher discrimination may be higher in areas with higher-performing schools.

“Discrimination is undermining choice in two different ways: where you can live and where you can go to school,” said Martha Galvez, principal research associate at the Urban Institute. “There is a direct line that you can tie between people’s housing opportunities and... economic and education opportunities.”

Policymakers, landlords, tenants, public housing authorities, and housing advocates all play a role in whether the voucher program lives up to its goals, but so do educators and those invested in education equity. On this topic, as with so many others, housing policy is education policy.

Voucher denials are higher in areas with lower poverty and higher-performing schools

Under the Housing Choice Voucher Program, participants typically pay 30 percent of their monthly income toward rent, and the federal government covers the rest. But just getting a voucher is hard, and finding a landlord to accept that voucher may be even harder.

“We don’t do Section 8 at all—not interested in that type of business.”

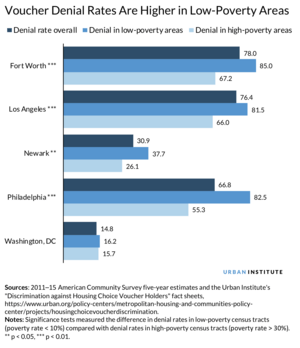

An Urban Institute study of housing voucher discrimination in five metropolitan areas found that 78 percent of landlords in Fort Worth said they did not accept vouchers. Denial rates were also high in Los Angeles (76 percent) and Philadelphia (67 percent). Newark and Washington, DC—both of which have laws protecting voucher holders—had lower denial rates: 31 percent and 15 percent.

California has since amended its fair housing law to include protections for voucher holders.

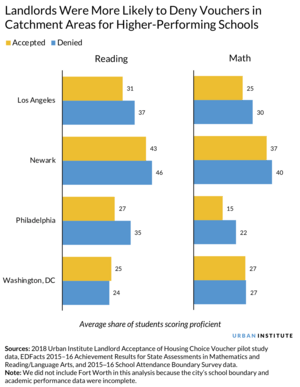

Across all five metro areas, voucher denials were more common in low-poverty areas than in high-poverty areas. And recent Urban research finds that in three of the four metro areas with complete data—Los Angeles, Newark, and Philadelphia—denial rates were higher in school catchment areas (i.e., school attendance boundaries) for higher-performing schools. (We did not include Fort Worth in this analysis because the city’s school boundary and academic performance data were incomplete.)

High-performing schools are defined here as schools where students tested proficient in reading and math tests. The graph below shows the average share of elementary school students who were proficient in reading and math in school catchment areas where a voucher was accepted compared with catchment areas where a voucher was denied. The same patterns hold true across middle and high schools.

In Philadelphia, in school catchment areas where a voucher was accepted, 27 percent of elementary students on average scored proficient in reading tests. And in school catchment areas where a voucher was denied, 35 percent of students scored proficient.

This research aligns with other studies showing that families receiving federal housing assistance, including vouchers, live near lower-performing and higher-poverty schools than other poor families with children—and this is especially true of Black and Hispanic voucher holders when compared with white voucher holders.

Although vouchers give families the opportunity to move to areas with higher-performing schools, half of voucher holders in 2016 lived near a school ranked in the bottom 27 percent within their state, based on school proficiency rates.

Voucher discrimination alone is not the sole barrier to entry for low-income families. Neighborhoods with higher-performing schools may not have enough available housing. But a 2019 study found that vouchers are more concentrated in higher-poverty communities than you might expect, based on the share of voucher-affordable rentals.

In the 50 largest metro areas, only 5 percent of voucher holders with children live in high-opportunity neighborhoods—defined by an “opportunity” measure that factors in school proficiency—even though 18 percent of all voucher-affordable rentals are available in those areas.

Federal law doesn’t protect against voucher discrimination, but many state and local laws do

Federal law does not protect voucher holders from discrimination, so several states and local jurisdictions have passed their own laws banning discrimination based on a person’s source of income.

But “just because a jurisdiction has source-of-income protection doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s a strong law or a well-enforced law,” said Philip Tegeler, president and executive director of the Poverty & Race Research Action Council. “In places where there’s a strong enforcement culture and a strong law, like Washington, DC, you see very low rates of voucher discrimination compared to other places.” The council recently published a guide to drafting effective source-of-income discrimination laws.

Caleb Roberts, northwest Texas codirector of Texas Housers, said the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) should take an even stronger enforcement role, holding back money from states without source-of-income discrimination laws. “You can’t be spending money on the voucher program and then have it confronted with an equal and opposite force,” he said. “It just doesn’t make any sense for what vouchers are trying to do.”

“Our company does not accept vouchers.… We do not have a person to take care of the vouchers.”

Two states—Texas and Indiana—ban localities from passing their own source-of-income discrimination laws. Rental property owners who supported the ban in Texas said that participating in the Housing Choice Voucher Program should be a choice, arguing that the longer leasing and inspection process and other administrative burdens and inefficiencies made working with the program a hassle.

Advocates working to overturn that ban argue that it allows landlords to discriminate by race and class—and that objections to vouchers are based in myths about voucher holder families.

“Vouchers have a stigma to them—a stigma of someone who’s lazy, someone who just lives off government assistance,” Roberts said. “[But that’s] not the people that we meet who have vouchers, who are working two jobs, supporting families.”

Residential segregation drives school segregation

Even though voucher use is not protected under the Fair Housing Act, many voucher holders are. In general, voucher holders tend to be disproportionately people of color, and disproportionately Black, compared with the populations where they live, and many are people with disabilities and families with children—all protected classes. And by design, voucher holders have low incomes.

So when landlords refuse to rent to families with vouchers, that discrimination holds back access to schools and diversity within schools, helping cement residential and school segregation.

“Historically, these two things have always been linked,” said Tomas Monarrez, research associate at the Urban Institute. “School segregation and neighborhood segregation are intertwined.”

Residential and school segregation aren’t accidents. These entrenched patterns stem from generations of racist policies and practices and intentional divisions by class and income that persist today.

The research is clear that school segregation harms students of color—when students of color attend segregated schools, they tend to have higher drop-out rates, lower test scores, more encounters with law enforcement, and worse outcomes when it comes to future income and long-term health.

Research has also found that more socioeconomically and racially diverse schools have benefits for all students, including academic outcomes such as better test scores and college attendance rates, economic outcomes such as higher earnings, and personal outcomes such as exposure to more complex classroom discussions and reduced racial biases.

Policy and program solutions

Addressing voucher discrimination and other barriers to school diversity and integration will require greater coordination between housing policy and education policy. Housing and education are managed by separate agencies at all levels of government, but many policy alliances, advocacy campaigns, and program partnerships are bridging that gap.

Housing and education advocates can also jointly seek policy and practice changes that would protect voucher holders from discrimination—such as source-of-income discrimination laws and enforcement—and make the voucher program easier for landlords and tenants to navigate.

“On a neighborhood level, you really need to have some strong, confident advocates who can get up in front of a meeting... and discuss the need for these conversations,” Roberts said. “Because at a neighborhood level, you can really change the landscape.”

HUD and public housing authorities could encourage landlords to take vouchers by strengthening financial incentives for first-time participants or landlords in low-poverty neighborhoods, setting more competitive rents, offering higher rent standards in more expensive neighborhoods, and extending the time voucher holders are allowed to search for a unit from 60 days to 120 days.

“I asked the agent if he accepted vouchers, and he said no. He has never been involved with Section 8 but has heard it takes a lot of time. He has a full-time job and does not have the time to go back and forth with Section 8.”

In HUD listening sessions (PDF), landlords said they wanted public housing authorities to provide more support and communication and expressed complaints about the speed and consistency of inspections. Being required to keep a unit open for a month or more is a burden for landlords, and a reason not to participate in the voucher program.

“To have better acceptance of vouchers in the private market, you really need a well-run, well-functioning customer-service-oriented public housing authority,” Tegeler said. “Some programs aren’t as responsive or as quick in processing, and that can be a real deterrent or turnoff to landlords.

In addition, voucher holders are largely left on their own to find a place that accepts vouchers. Some PHAs and neighborhood mobility programs offer housing search assistance to help voucher holders identify good neighborhoods with good schools and support their transition.

“These areas of opportunity are far out of the wheelhouse for a lot of these residents. They don’t know anything about these places… so it’s scary for them to go out there,” Roberts said. “It is really difficult because [they’ll say] ‘well, my family is here,’ or ‘I take care of my mother some days, so if I’m all the way out there, how will I do that?’”

Baltimore, Dallas, and Seattle, for example, offer neighborhood mobility support, though most housing authorities don’t have the resources to do the same.

Market factors also affect landlords’ willingness to accept vouchers. Until vouchers operate as smoothly for landlords as taking any other payment method, they may prefer to opt out of the program if they have assured rent receipts without it. The economic fallout from COVID-19 may make landlords more interested in a government-backed rent payment, Galvez said, so housing authorities may be able to leverage that interest to encourage participation in the voucher program even after the crisis passes.

Achieving the goals of the housing voucher program

Despite the problems with the housing voucher program and the high denial rates in neighborhoods with high-performing schools, vouchers still provide tremendous value to families.

“For the people who use vouchers, they have an incredibly important impact... in terms of economic security and housing safety and stability,” Galvez said.

“There’s this one goal for the program that has always been implicit and it’s never been achieved: neighborhood mobility.... If it’s going to be achieved, it’s going to take more explicit attention. And it’s not going to happen all by itself.”