Image courtesy of VMDO Architects

“Not All Parks Are Created Equal”: How Communities Can Ensure Parks Are Accessible for All Residents

For the children living in Washington, DC’s Dupont Circle, a typical Saturday trip to Stead Park involves frolicking on the splash pads or swinging on the playground while their parents watch from a nearby bench. But it didn’t always look like this. In 1988, several neighborhood kids went to the park to play one weekend and found themselves as part of a volunteer crew instead, fixing water fountains, benches, and swing sets in the park that news articles at the time described as “overrun” by “vandalism and neglect.”

Kyle Mulhall, now the commissioner of Advisory Neighborhood Commission 2B09 and a board member of Friends of Stead Park, moved to Dupont Circle in 1983. He remembers that back then, the park was nothing more than a dirt field, a basketball court, and a small playground.

“It just was a complete afterthought,” Mulhall said. “You’d talk to people who were relatively well-established residents of the neighborhood who—even though you’d be sitting on 17th Street—would be surprised when you’d tell them there was a park behind the building.”

In the decades since Mulhall moved to Dupont Circle and those kids were enlisted as the park cleanup crew, Stead Park has undergone three rounds of renovations—in 1992, 2008, and 2014. DC’s Department of Parks and Recreation replaced the dirt field with turf, spruced up the playground, and added splash pads to help residents cope with the heat. Rather than an “afterthought,” the park became more of “a central feature of the neighborhood,” Mulhall said.

Image courtesy of VMDO Architects

Stead Park’s evolution from dirt field to community staple in part embodies what equitable park access means. In the 1980s, Stead provided communal green space for a dense part of DC, but it lacked the amenities that would make it useful for the community. Although residents lived in close proximity to Stead, the park was underused, as it didn’t meet their needs.

“Not all parks are created equal,” said Kimberly Burrowes, a technical assistance manager in the Research to Action Lab at the Urban Institute. “When you look at park development, maintenance, and even programming, you realize that access is more than just spatial.”

Ensuring that residents have equitable access to parks, including facilities and programming that fit their specific needs, can have profound positive effects. Parks serve many purposes, Burrowes said, and provide nearby residents with health, environmental, and social benefits. In this way, parks and housing are linked: the green spaces provide residents health and social benefits that may not be offered by an apartment building or single-family home. Having a private green space or a balcony is a luxury many can’t afford, so where you live determines the green amenities you can access.

For local policymakers, understanding a community’s needs and working to meet them can lead to better health and housing outcomes and a more equitable distribution and construction of parks and green spaces.

What does equitable park access look like?

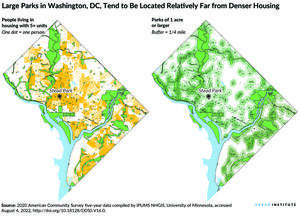

For DC residents, proximity to a park isn’t usually a problem. All types of parks exist in the city, with very few residents living more than a 10-minute walk away from one. But whether the closest park fits a resident’s needs is a different matter. In the denser parts of DC, where multifamily housing is common, parks tend to be smaller and have less tree canopy, meaning people who are most in need of communal green space lack sufficient usable access to it.

Parks also have a long history of discrimination in the US. Racial covenants and redlining enforced segregation of green spaces and have often led to lower-quality, less-maintained parks in predominately Black neighborhoods. Recent research has found that parks serving primarily people of color were half as large and five times more crowded than parks in majority-white communities. Large parks and those with multiple uses for diverse groups of people are often located far from denser neighborhoods.

In DC, residential segregation was influenced by the location of amenities like parks. That is, white people wanted to live near the large green spaces, effectively blocking others from doing the same. DC has a fixed amount of space, and competition for that real estate means parks, housing, and other types of land use have to fill a wide range of community needs.

Centering equity in parks for people who’ve been systematically excluded from accessing those spaces entails more than just meeting their needs; it also requires building a sense of identity and belonging.

So how can cities and neighborhoods tailor their green spaces to better suit their residents, build belonging, and create equitable outcomes? Based on research from the Urban Institute, the following recommendations offer strong first steps.

Conduct extensive community outreach

For a park to be successful, the first step must be understanding how a community uses the space. If the neighborhood has many young families, the park should include a playground and benches. If the neighborhood includes many older residents, the park should center accessibility and offer community events. Younger people might want sports fields, and people in dense neighborhoods might prefer more tree canopy and shade. Neighborhoods will often include residents from many backgrounds with different needs, so policymakers and park practitioners can ensure parks reflect all their priorities by conducting extensive outreach to understand who is living and working in close proximity.

“There should be so much effort and time invested by the city in just ensuring that all park users and people who are potentially park users have their voices really reflected,” said Matt Eldridge, a senior policy program manager in the Research to Action Lab at the Urban Institute. “Parks are so widely used in such a democratic way that they provide a blueprint for what collaboration can look like.”

Often, when parks are underused or inaccessible, it’s an indication of a power and resources imbalance in the neighborhood. As Eldridge explained, some parks that are well utilized and appreciated by community members might have limited resources for maintenance and programming, which can impose challenges to parks’ access and sustainability.

But when groups do have the resources to invest in a park, it should be done intentionally and include residents’ opinions, even if it takes longer. That way, park users are empowered as owners and stewards of the green space, and the park can become a place to break down inequities rather than reinforce them.

Examine thorough local data

Along with comprehensive community outreach, park practitioners also need to identify and analyze what local data can tell them about the role parks play for locals. With data, park practitioners can make a better case to policymakers that parks need additional investments and can guide where those investments should be targeted.

Data on park equity requires more than just measuring how far residents live from a park. Although proximity is often a good indicator of access, when park practitioners assess who is using a park, not just who lives close to a park, policymakers have a better understanding of how equitable a park is. Robust local data can also highlight several other park benefits: tree canopy and use of permeable surfaces offer environmental benefits, ballfields and active spaces provide opportunities for physical recreation, and communal spaces for gathering can support diverse programming targeted to locals.

Image courtesy of VMDO Architects

Regularly assessing programming, park use, and park conditions can help determine park quality. In a large and well-resourced city like DC, open data sources may already exist. But actual on-the-ground data collection can still enhance understanding of uses and users or document park amenities and conditions. Working with local stakeholders, whether through more traditional community engagement and outreach or through direct data collection and reporting, offers an avenue for understanding how parks can benefit residents and support their needs.

Forge partnerships and explore multiple funding streams

Conducting outreach and accessing relevant data requires a lot of time and ample funding. And parks are usually the first line item to see cuts when budgets need trimming.

“Park departments often have to cobble together creative funding sources,” Burrowes said. But, she added, parks also sit at the intersection of multiple policy areas, meaning policymakers can get creative and “double dip” into other pots of funding. For instance, many parks are rights-of-way, connecting one community to another. These parks could access US Department of Transportation funding to maintain the space. Parks, along with health care systems, also improve residents’ well-being, and park practitioners could partner with local health organizations to offer programming or to raise funds. Creativity and the willingness to explore different types of funding can help practitioners work with policymakers to improve green spaces in spite of often-insufficient budgets.

Leverage temporary-to-permanent innovations

So much work can be done on the front end to create designs informed by community input and data, but how a park will be used in practice can’t be seen until the changes are implemented. To better understand how residents might use a park or green space intervention, park practitioners can use temporary-to-permanent strategies to pilot investments in the community. Policymakers can make more flexible resources available for this type of testing to offer local solutions in a phased approach to instigate change.

“There’s no way that every single resident and every single user might be able to contribute to the park’s design, but what they can do is see some of the investments in a temporary way,” Burrowes said. To be successful, pilot investments need a reasonable amount of time to generate data. If the community doesn’t have enough time to use and adapt to the new installments, they could be removed before any potential benefits surface.

These sorts of temporary changes have been made before: in spring 2020, the National Park Service closed some of the roads through Rock Creek Park in Northwest DC to motorized traffic. Although the change led to increased recreational use and though residents have favored keeping the roads closed, the National Park Service has proposed a partial reopening where cars would only be prohibited on weekends and during summer weekdays. This misalignment highlights the special case of DC, where federal government authorities aren’t directly beholden to residents or governments.

How policymakers are taking these steps to make Stead Park more accessible for all residents

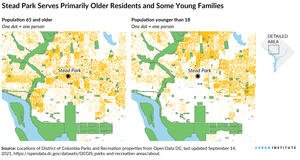

Part of Stead’s renewal has come as the neighborhood surrounding it has changed. Whereas Dupont Circle was a predominately Black neighborhood when the park opened in 1953 (PDF), today, its residents are more diverse. More young families and people in their twenties have moved into the neighborhood, according to Mulhall, and have become the primary demographic for the park. The families use the playground and splash pads while the young people use the basketball court and the playing field for softball, kickball, and soccer leagues.

“It’s almost a generational difference,” Mulhall said. “The older folks that moved into this neighborhood in the 60s and 70s and, to some degree, in the 80s are less likely to be users of the park.”

As Stead Park has changed over the past few decades, it’s emphasized these great opportunities for activity and socialization new residents have wanted. But Stead still has room to improve. It lacks tree canopy, some of its equipment has fallen into disrepair, and it doesn’t have as much programming for the area’s older residents, according to Mulhall.

There is also the question of who isn’t using the park. Within a 10-minute walk of Stead, there are dozens of businesses and restaurants, a Metro station, a local food bank, and N Street Village, which houses people experiencing homeless. People who frequent each of these places could also become park users if they feel welcome in the space. To address inequities in park access, local leaders should consider how to include those who have been left out of a space’s narrative.

To improve the park with these needs in mind, DC’s Department of Parks and Recreation is renovating Stead Park to build a new community center to add programming space for older residents, new playground equipment for area kids, and more shaded areas and trees to make the park more usable and reduce the urban heat island effect. To increase the park’s sustainability, the community center will be the parks department’s first LEED Platinum–certified structure, and solar panels will be installed on its roof.

These improvements and their final designs were the product of multiple years of community outreach, including 10 open community meetings, nearly two dozen workshops with community stakeholders, two surveys totaling 652 responses, and direct outreach to 16 organizations that either use the park or are located nearby. Mulhall would even go down to the park during the day to talk with the parents who brought their kids out to play.

Image courtesy of VMDO Architects

Although the renovations are expensive, at an estimated cost at $15.4 million, Mulhall says these changes are just the next phase of the ongoing Stead Park rejuvenation. Friends of Stead Park, a community advocacy group that supports the park, is contributing half a million dollars because they see the value in keeping the park up-to-date and usable for the community.

Future renovations will likely focus on repairing the playing field and creating a more-welcoming second entrance to the park off of the pedestrian-heavy 17th Street. For the latter suggestion, Mulhall points out that 17th has already experimented with closing off part of a dead-end street to add table spaces for restaurants in the area, which has been highly popular. That space could also be reclaimed to make a larger, more visible entrance to Stead Park.

Through community outreach, data collection, combined funding streams, and piloting projects, the Stead Park renovations have worked to build a sense of identity at the park and to connect the community to the green space. But the work never ends.

“The park shouldn’t be in isolation, it should be all tied in,” Mulhall said. “And most of us are thinking about this as not just a one-and-done, but a great next step. And then let’s see what we can do to continue to evolve the neighborhood.”

Image courtesy of VMDO Architects