“The Future Is Shared”: Why Supporting Renters during COVID-19 Is Critical for Housing Market Stability

Steve Thomas has operated as a small landlord on the South Side of Chicago for 25 years. Most of his tenants are single mothers living paycheck to paycheck and working low-wage jobs. With employers across the country implementing massive layoffs during the COVID-19 pandemic, most tenants who lose their jobs don’t have enough savings to cover next month’s rent, let alone the next several months’.

“I really don’t know where that leaves us, but I know it leaves us vulnerable,” Thomas said. “It leaves us all vulnerable.”

“If you start getting nothing but institutional owners in these predominantly low-income neighborhoods, it’s going to be problematic.”

Thomas is worried about the future of his 18-person company, 5T Management, as well as the future of his tenants if his business shutters and a new investor unfamiliar with the area takes over his buildings. “If you start getting nothing but institutional owners in these predominantly low-income neighborhoods, it’s going to be problematic,” he said. “People who have money sitting on the sidelines could come in, buy deals, and force out the ma and pa landlords. You’d end up with a lot of fraud and a lot of people living in unsafe, unsanitary environments.”

The pandemic has spotlighted gaps in the housing safety net that left renters at risk long before this crisis and that will worsen as more people lose their jobs and face unexpected costs. But when tenants can’t pay their rents, they aren’t the only ones facing financial instability. Most landlords, especially smaller owners, operate on tight margins and can’t sustain a massive drop-off in rent payments for long. They could risk defaulting on their mortgages, missing insurance payments, or failing to pay city taxes—which, in turn, could destabilize the broader community.

That’s why policy solutions at the federal, state, and local levels need to keep the entire housing ecosystem in mind: when tenants can pay rent, landlords can maintain their rental properties, pay their underlying mortgage, and keep housing opportunities open for current and future renters.

“It’s all interconnected in a circle of life,” said Monique King-Viehland, director of state and local housing policy at the Urban Institute. “To address the crisis from an equitable framework, we need to recognize that interconnectivity and implement policy and practice around that.”

Renters, landlords, and affordable housing are at risk

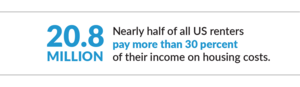

Renters were already struggling to make ends meet before the pandemic. In 2018, nearly half (20.8 million) of all US renters paid more than 30 percent of their income on housing costs, and a quarter of all renters (11 million) paid more than half their income on housing.

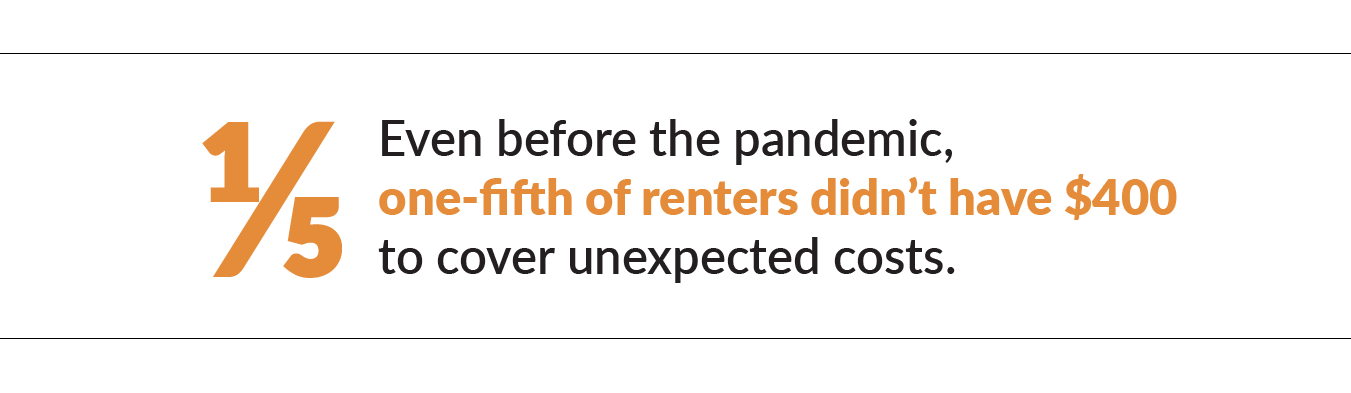

Renters are less financially stable than homeowners, with lower incomes and more income volatility. They’re also less prepared to deal with a sudden emergency or income loss like the one many Americans are facing now; in 2018, one-fifth of renters reported that they didn’t have $400 to cover unexpected costs. And low-income renters are more likely to lose their jobs during the pandemic because many work for service industry businesses that are furloughing workers.

The US Department of Housing and Urban Development offers rental assistance, such as vouchers and public housing, to help ease people’s housing cost burden. But those programs have been chronically underfunded, and as of 2016, only one in five renters who qualified for and needed housing assistance received it.

With a record number of people filing for unemployment amid the pandemic, the number of renters who need help meeting their basic needs is likely to skyrocket. And without financial assistance, these renters face the risk of homelessness or overcrowding in the homes of family or friends—situations that carry severe health risks during a pandemic. These risks are even greater for people of color, as Black and Latinx people are more likely to be renters and to work in the service sector.

The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, passed by Congress in late March, included funding (which some groups say isn’t enough) to ensure the nearly five million households who already received housing assistance before the pandemic continue to receive that assistance and that the amount the government pays toward their rent increases if they lose their jobs.

But the CARES Act doesn’t offer housing assistance designated specifically for the remaining 18 million low-income renter households who already qualify and need assistance but don’t receive it, nor does it cover the growing number of renters who will suddenly need help as businesses shed jobs. The act’s one-time $1,200 check can help in the short term, but there’s no clear end date for this pandemic. Without additional money coming in, that amount won’t cover a few months’ rent for most people, even for the renters who live in the 50 percent of unsubsidized rental units in the US that cost less than $1,000 a month.

“We’re concerned about our whole portfolio of properties. You never think about that as a possibility. You think about a fire in one building, and you have insurance for that. But not for this.”

The CARES Act does include an eviction moratorium for some renters (federal agencies are protecting a much larger share of homeowners from foreclosure), and many cities and states are enacting their own moratoria to fill gaps in eviction protections for renters. But eviction moratoria aren’t enough. Eventually they end, and renters could find themselves on the hook for multiple months’ rent. Given renters’ economic precariousness before the pandemic, many may not have enough savings to pay back all that rent to their landlords.

Because the situation is changing so rapidly and the economic effects of COVID-19 are expanding every day, the share of tenants who won’t be able to pay their rents in the coming months isn’t yet clear. But many property owners trying to communicate with their tenants to find out how the pandemic is affecting them are bracing for massive losses in rent for the foreseeable future.

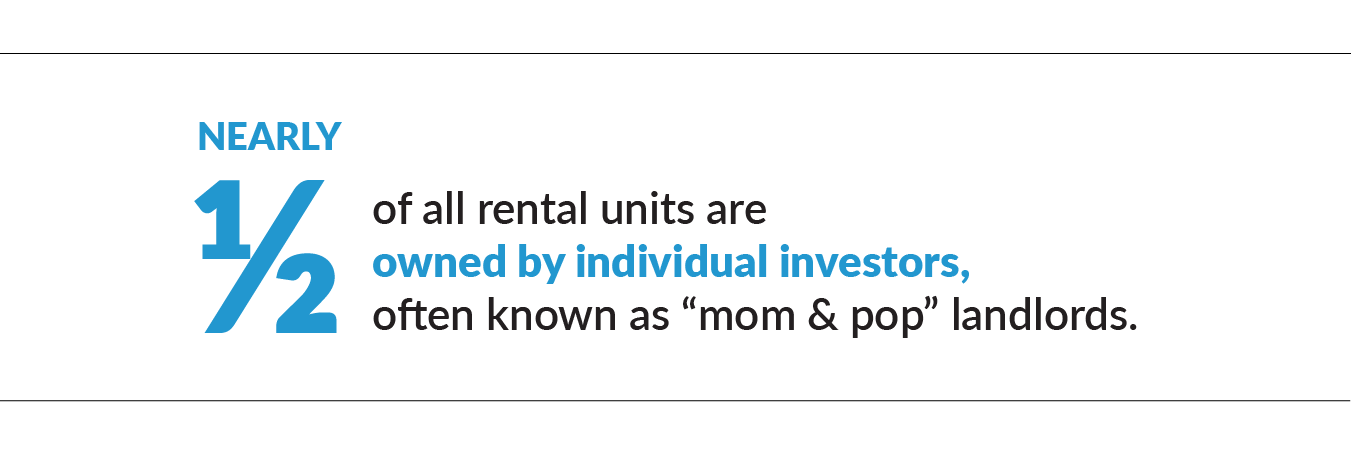

Not all landlords are large organizations with huge operating reserves. Nearly half of all rental units are owned by individual investors, often known as “mom and pop” landlords. Most building owners, especially landlords who offer affordable units, have narrow profit margins. Thomas said that, after all expenses are taken into account (except capital expenditures), he makes around $100 profit per unit each month.

“There’s a perception that property owners are flush with cash,” said Eiran Feldman, president of First InSite Realty in Chicago. “At the end of the day, there are a lot of small operators, a lot of family businesses, and this is their livelihood. They also do it with a lot of care and passion, and they’re under tremendous stress and tremendous responsibilities. This industry is very fragile.”

When those smaller landlords with less operating reserves don’t have steady rent payments coming in, they could face the risk of not being able to repair or improve their properties and missing utility payments or property taxes—which could result in their units being taken away from current or future renters.

Before the pandemic, the US was already facing a severe shortage of affordable housing. If the nonprofit and for-profit owners who currently operate affordable housing lose this ongoing revenue source, the country could risk losing some of the few affordable housing options it does have. And there’s no guarantee the investors who buy those properties would keep their units affordable or maintain them at the same quality.

Nina Janopaul, president and CEO of the nonprofit Arlington Partnership for Affordable Housing, said owners, especially affordable housing operators, are facing an unprecedented threat. “We’re concerned about our whole portfolio of properties. You never think about that as a possibility,” she said. “You think about a fire in one building, and you have insurance for that. But not for this.”

Policy solutions to help everyone in the rental housing ecosystem

Acting quickly is critical to stabilizing the entire housing ecosystem. Many tenants couldn’t pay rent on April 1, and they will likely struggle to come up with rent payments for the next several months as the pandemic’s effects continue to grow.

“I hope help is deployed to provide immediate response,” said Hal Ferris, founding principal at Spectrum Development in Seattle. “Overreaction is better than cautious and slow reaction.”

Even though the CARES Act didn’t include funding dedicated solely for rental assistance, state and local governments can use the act’s flexible funding to stabilize renters. And in future federal legislation, lawmakers can ensure all renters in need can stay in their homes throughout the crisis and beyond by offering additional emergency rental funds and ensuring that the resources can provide ongoing assistance.

“State and local governments are going to have to figure out, now that we know what the federal government is going to do, where the gaps still lie. And based on that, what are the things state and local governments can do, and what advocacy at the federal level is still needed to fill those gaps?” King-Viehland said.

Solutions to quickly respond to the pandemic

In the short-term, federal policymakers can create a dedicated emergency rental assistance program or expand the Emergency Solutions Grant (ESG) program to cover the growing number of renters in need. Through the current ESG program, public and nonprofit social service agencies across the country field renters’ requests for emergency assistance and distribute available federal and state funds to landlords to cover documented shortfalls. Without additional funding, these programs will run out of resources amid the sharp uptick in tenants at risk of eviction during the pandemic.

Federal policymakers can also ease guidelines for this short-term emergency assistance that require tenants to prove that the funding resolved their risk of housing instability in a certain timeframe. Because of the uncertain nature of the pandemic, tenants’ housing stability risks have no clear end date.

“There are going to be crises after this. Ultimately, we’re going to have to stand up something permanent.”

Also at the national level, the Federal Emergency Management Agency could broaden the definition of “disaster” to include the pandemic, allowing localities to use their disaster relief funding more flexibly.

At the state and local levels, policymakers can use flexible funding in the CARES Act (specifically, resources for the Community Development Block Grant, Emergency Solutions Grant, and the Coronavirus Relief Fund) as well as their own funding sources (like housing trust funds) to stabilize lower-cost rental housing through bottom-up financial support that assists renters directly or that assists property owners with stipulations about passing relief on to their tenants.

State housing finance agencies (HFAs) can use their lending tools to assist landlords who are not yet covered by mortgage forbearance. Property owners with low-income tenants could work with an HFA to refinance their mortgage and obtain a delayed repayment period in exchange for incorporating rent relief (such as allowing for tenant repayment plans). These types of programs can reach small landlords by partnering with community development financial institutions to assist in implementation.

State and local governments can also encourage renters and landlords to meet virtually with a trained mediator who can assist each party in communicating their needs. Mediation can help ensure repayment plans are realistic for the renter by including partial payments and a timeline that builds in uncertainty about how much income loss renters are facing and for how long. These efforts can be informed by lessons from the foreclosure crisis, when research found benefits of automatically scheduled mediation sessions, and housing counselors said mediation led to better outcomes than negotiations without a mediator.

Longer-term solutions to help recover and build resilience

Stabilizing renters—which, in turn, supports landlords and rental properties—is critical. But policymakers can leverage this opportunity to implement long-term solutions that reduce the number of renters at risk and ensure the housing market is better equipped for another unexpected crisis.

“A lot of the action so far has been short term. It could all terminate in several months even though we could still be in the midst of a recession,” said Douglas Rice, senior policy analyst at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. “We’re facing a cliff several months down the pike that needs to be addressed.”

“If we’re not taking care of folks on both ends, we’ll fail. There needs to be balance, because the future is shared.”

To offer more long-term relief, federal policymakers can designate housing as an entitlement and fully fund universal rental assistance to help all low-income renters at risk.

State and local policymakers can supplement those federal efforts by implementing a more modest form of rental assistance, possibly through a no-interest loan or through the ESG, for people who may not experience as severe an income loss but who are still burdened by their housing costs.

“There are going to be crises after this. Ultimately, we’re going to have to stand up something permanent,” said Mike Koprowski, national campaign director at the National Low Income Housing Coalition.

Policymakers at all levels of government can also ensure that, when development ramps up again, affordable housing production is prioritized. Aaron Gornstein, president and CEO of Preservation of Affordable Housing, said an increase in subsidies like those through the Low Income Housing Tax Credit and the HOME Investment Partnerships program could help encourage investors to focus on affordable housing construction and help meet the growing demand for affordable units.

“Once we get through this initial crisis, the need for affordable housing is going to be even greater,” Gornstein said. “There may be new opportunities to preserve and produce more affordable housing with additional resources and greater public attention. This will not only help to provide safe, healthy, and affordable homes for those who need them, but it can provide a powerful stimulus to our economy, which is likely to be in a recession.”

Ensuring a holistic approach to stabilizing the housing market

Federal response to the COVID-19 pandemic so far has not prioritized most renters, including those who already had low incomes and were rent burdened and who are now at risk of losing their jobs and being unable to pay rent entirely. States and localities, as well as future federal legislation, need to fill in the gaps to help stabilize renters, their landlords, and the housing market as a whole.

“If we’re not taking care of folks on both ends, we’ll fail,” King-Viehland said. “There needs to be balance, because the future is shared.”

Project Credits

POLICY ANALYSIS: Maya Brennan and Martha Fedorowicz

RESEARCH: Nicole DuBois, Corianne Scally, and Kathryn Reynolds

DESIGN: John Wehmann

DEVELOPMENT: Jerry Ta

EDITING: Alexandra Tammaro

WRITING: Emily Peiffer