What Can State and Local Governments Do to Stabilize Renters during the Pandemic?

The first weeks of the COVID-19 crisis have brought widespread unemployment that many believe will get worse, especially for low-income renters. State and local governments are on the front lines responding to the housing needs of households affected by COVID-19, but they are working without a clear playbook for delivering housing assistance at this unprecedented scale and are relying on local service delivery systems that were not designed to respond nimbly to surges in demand. Nevertheless, state and local governments are improvising and innovating—adapting existing housing assistance models and devising new ones to try and stabilize low-income households affected by COVID-19.

They face an uphill battle and sorely need more support from the federal government. But as state and local governments begin to mobilize funds already coming down through the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act and design their own policies and programs, they can look at past lessons and emerging approaches to meet the challenge.

What challenges do low-income renters face?

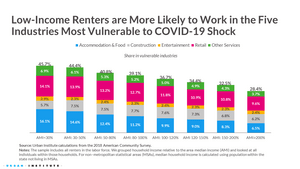

Almost half of the lowest-income renters (those earning less than 30 percent of the median income for their jurisdictions) work in the hardest-hit industries, including accommodations and food, retail, construction, entertainment, and other service jobs.

Job and income losses threaten to bring a second crisis of unpaid housing debt and displacement, with warning signs already visible. On April 1, more than $49.4 billion in rent payments were due, but as of April 12, only about 84 percent of these payments had been made either fully or in part. This was about 6 percentage points lower than the share that had been made by the same time in March or in April of last year.

Rent payments come at great cost to struggling renters who’ve lost their jobs, have low to no savings, and may already be forgoing other basic needs, such as food and medical care. The number of households unable to pay rent will likely increase as the crisis continues—especially among those who are not covered by unemployment insurance or who struggle to access it (such as gig economy workers, self-employed or part-time workers, independent contractors, and undocumented immigrants). For others, unemployment benefits won’t cover their actual financial needs. Meanwhile, racial disparities in education, employment, and wealth will contribute to worse housing outcomes among communities of color.

Eviction moratoria delay the inevitable

Currently, state and local policy responses to housing instability focus mainly on emergency orders to prevent homelessness and pausing evictions with temporary moratoria. But landlords rely on rent to pay their debts and operating costs, so moratoria will eventually lift and rent will again be due. Each moratorium is unique, and when they are lifted, it is not clear what will happen to millions of renters who may be accruing rent debt.

Federal help for renters from the CARES Act is limited. It mandates eviction moratoria for federally financed properties—but that’s just one in four US rental units. The CARES Act also provides approximately $12 billion for emergency housing and rental payments through existing federal programs administered by state and local governments (for housing choice vouchers and public housing, Community Development Block Grants, homeless assistance grants, and tribal housing programs). But the rental program funding will mainly cover people who already receive housing assistance and will only meet needs temporarily.

New funds will be needed to help address the needs of millions of households who are dealing with job loss and may be facing eviction, and who are not connected to existing housing assistance systems. Some additional federal emergency funding has been proposed, but it isn’t clear how much funding will be available, when, or how funds might be distributed.

State and local governments can step in to support renters

In the interim, state and local governments must plan for a COVID-19 “rent cliff,” or even the most aggressive federal relief efforts will be insufficient to stop widespread housing instability or evictions. Without intentional design and attention to infrastructure and capacity, states and cities risk overburdening existing systems that have seen declines in federal funding and that are already overtaxed.

Or, without explicit attention to racial equity, they may rely on systems that have historically exacerbated inequalities and excluded some of the most vulnerable renters and communities. We already see this happening. Black and Latino households were already more likely to be rent burdened or homeless before the pandemic when compared with white or Asian households. Now, Black and Latino people are dying at higher rates from COVID-19.

As part of the Urban Institute’s exploration of policies to protect people and places from the impacts of COVID-19, over the next few weeks a team of researchers will be examining how state and local governments can respond to the tremendous rental housing challenges presented by COVID-19. In this blog series, we will present promising strategies to help states and local areas equitably answer, “What do we do when the rent is due?”

Questions include:

- How can federal policies and programs bolster state and local housing infrastructure and capacity to effectively deliver assistance to vulnerable renters?

- What can state and local governments learn from existing housing assistance models to deliver emergency housing to those who need it most?

- What are state and local governments doing now to assist renters affected by COVID-19, what are the features of new rental assistance programs, and what can we learn from them?

- What legal protections need to be in place when moratoria are lifted to prevent a surge in evictions?

COVID-19 has brought unprecedented challenges to the nation’s health, housing, and safety net service delivery systems—the full extent of which is not yet fully known. Navigating these challenges and protecting vulnerable households from job loss and housing insecurity will require channeling the very best of existing models, as well as new funding and approaches.

Photo by artazum/Shutterstock