(MattGush/Getty Images)

The Wealth Gap between Homeowners and Renters Has Reached a Historic High

This post was originally published on Urban Wire, the blog of the Urban Institute.

Homes are often families’ largest assets and one of the most effective ways to build wealth, but countless news stories and studies detail just how out of reach homeownership has become. What does that mean for the wealth gap between owners and renters?

The most recent Survey of Consumer Finances data reveal that in 2022, both the median and average wealth gaps have reached historic highs since the data were first collected in 1989:

- In 2022, the median wealth gap between homeowners and renters reached almost $390,000, and the average wealth gap reached over $1,370,000.

- Over the past 33 years, the median wealth gap between homeowners and renters has increased by 70 percent, while the average wealth gap increased more than 250 percent

- During this period, homeowners' median and average wealth increased by almost $165,000 and $900,000, respectively. But for renters, the increases were $5,800 and $56,000, respectively.

The Wealth Gap between Owners and Renters Has Reached a Historic High

Source: Survey of Consumer Finances.

Note: Wealth adjusted to 2022 dollars using the Consumer Price Index.

The significantly wider gap in average wealth (compared with median wealth) indicates that a large share of wealth is concentrated among a small share of households. Because of this, in a new analysis, we explore the reasons for the median wealth disparities, which better reflect differences among typical homeowners and renters.

We find that recent housing wealth gains are largely driving median wealth disparities. Because of supply shortages, home price went up, and rent prices also increased faster than incomes. This resulted in a higher housing cost burden among renters. Left with limited savings after paying for housing, renters have also not benefited from the strong financial market in the past several years, which further fueled the gap.

Boosting the housing supply is critical to ensuring the housing and financial wealth gaps between owners and renters don’t further widen.

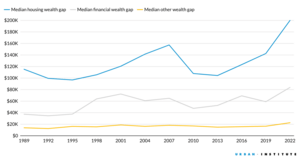

The housing wealth gap is driving overall wealth gaps between owners and renters

Housing wealth accounts for the highest portion of the wealth disparities between homeowners and renters—and this portion has increased substantially over the past 10 years. Fluctuations in home prices are highly correlated with the housing wealth gap.

From the mid-1990s until 2007, the median housing wealth gap increased but then declined significantly when home prices dropped during the housing market crisis. But as supply fell substantially short of demand following the Great Recession, home price increases have accelerated, leading to huge home equity gains for those who were able to sustain or access homeownership during the past 10 years.

While homeowners experienced significant wealth gains, renters found it more challenging to access homeownership, as more and more affordable housing disappeared from the market.

Housing Wealth Has Fueled the Wealth Gap between Homeowners and Renters

Source: Survey of Consumer Finances.

Notes: Wealth adjusted to 2022 dollars using the Consumer Price Index. Adding the median wealth gap for the three categories is smaller than the overall median wealth gap because of the distribution of the three wealth categories. Financial and other wealth, which includes business assets, nonresidential real estate assets, and other types of assets such as automobiles, are significantly skewed toward the upper end of the distribution, especially for homeowners. Housing wealth is also skewed toward the upper end of the distribution but to a lesser extent.

Renters have less income to save and invest after paying for housing costs

Over the past decade, rental prices have increased faster than incomes, reducing renters’ residual income after paying for housing. In 2022, the share of renters spending more than 30 percent of their income on rent reached a record high, with about half of renters being rent burdened.

This is reflected in the median housing-cost-to-income ratio, which also increased during the pandemic. Compared with 30 years ago, the median housing-cost-to-income ratio has increased by about 5 percentage points for renters, but for homeowners, this ratio has declined.

The Median Housing-Cost-to-Income Ratio Has Increased for Renters and Declined for Homeowners

Source: 1990 and 2000 Decennial Census and 2001–22 American Community Survey data.

Note: Annual data are available from 2001.

This suggests that homeowners were able to save more after paying for housing costs than renters were.

Less savings can also lead to differences in financial wealth, differences that also increased during the pandemic. Between 2019 and 2022, homeowners’ median financial wealth increased from $60,000 to $85,000, while the overall median financial wealth for renters remained almost the same (around $960). Since 1989, renters’ median financial wealth has ranged from $400 to $1,200, suggesting that most renters do not actively invest in financial markets.

Potentially further fueling the trend, homeowners have the option to refinance and lower their housing costs when interest rates decline. The refinance volume surged during 2020 and 2021 when the mortgage rate hovered around 3 percent, giving homeowners another chance to decrease monthly housing expenses and invest their savings that renters don’t have.

More housing supply is needed to mitigate the growing wealth gap

Without increasing both the owner-occupied and rental housing supply, the growing wealth disparities between homeowners and renters are likely to persist.

A recent Redfin survey finds that more than a third of young homebuyers plan to use a cash gift from family to fund down payments, suggesting that intergenerational wealth may fuel gaps among the next cohort of homebuyers. In other words, if the housing supply fails to keep up with demand, households with financial resources will continue to build wealth with almost no effort. Meanwhile, households with limited ability to build wealth—who are most likely to be households with lower incomes and households of color—will remain renters and face higher housing costs that further restrain their ability to save for future homeownership.

To solve this problem, we need a comprehensive approach to increase supply, while providing financial support for renters to enhance access to homeownership

To increase affordable housing, more states could end statewide single-family zoning. Cities could also eliminate single-family zoning districts and legalize infill housing (e.g., two-to-four-unit buildings and accessory dwelling units) in single-family lots.

Though zoning and land-use regulations are local policies, the federal government can encourage these changes. The Biden administration recently proposed rewarding grants to local and state governments that work to reduce or eliminate zoning barriers to building housing. The federal government can also improve financing access and encourage jurisdictions to ease zoning restrictions for manufactured homes, which could add a meaningful supply of affordable housing.

But increasing the housing supply will take time. In the interim, the federal government can reduce rental cost burdens, especially for renters with low incomes, by expanding housing choice vouchers, to increase savings for down payments or financial investments. It can also provide targeted down payment assistance for first-generation homebuyers, who lack generational wealth.

Improving the financial security of renting and expanding homeownership opportunities—while boosting housing supply—will help realize more equitable futures for all.