Seeking Diversity to End Segregation

by Maya Brennan

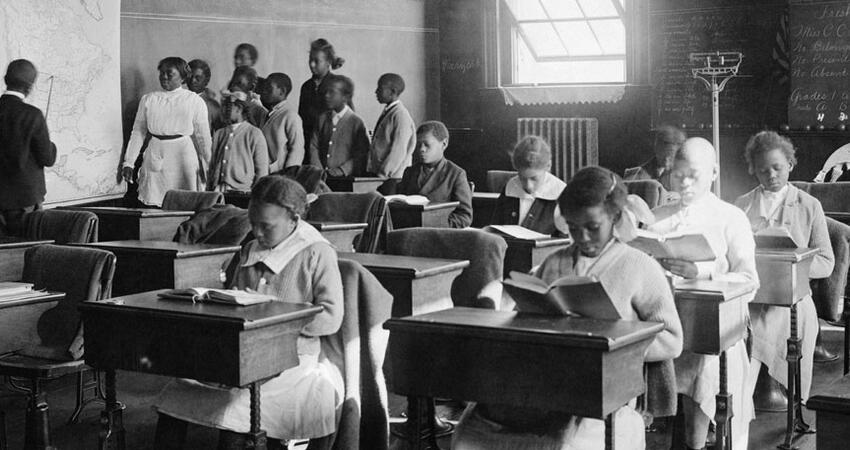

Place a dot in the center of Virginia, and you have likely hit Farmville in Prince Edward County. The town of a little more than 8,000 people entered the national spotlight as host of the 2016 vice presidential debate. Sixty-five years ago, however, the town was the setting for a different historic event: a high school walkout protesting the poor conditions for blacks in the town’s segregated schools. The resulting lawsuit was eventually incorporated into Brown v. Board of Education.

The county’s reaction? Shut down the public school system rather than accept integration.

Private schools opened with county support to fill the gap for white children. Although the public schools eventually reopened and integrated, many white families continue to opt out. According to a recent Washington Post story, while the county’s population is around 64 percent white, white children account for about 37 percent of the student body in the county’s public schools.

Schools are just one of many places where the remnants of the separate-but-equal era can still be seen. Job access, health care access, residential locations, home price appreciation, poverty, and community-police relations all look different depending on skin color.

Research from the How Housing Matters initiative has documented disproportionately high eviction rates among black women in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and higher eviction rates in the city’s high-poverty and majority–African American neighborhoods compared with high-poverty and majority-white neighborhoods. Institutional racism and the legacy of disadvantage may be combining with patterns of racial segregation to foster instability in households and neighborhoods.

In collaboration with other interrelated systems, housing can do better to advance racial equity, but the housing and community development world—and each of us as individuals—need to “get comfortable being uncomfortable.”

Individual Decisions Are an Important and Movable Contributor to Segregation

To understand the importance of individual decisions on racial segregation, look no further than a tool released a few years ago that turns Thomas Schelling’s work on segregation models into a game called Parable of the Polygons. The game shows that a small preference to be among similar shapes will lead to clear patterns of segregation. Once segregation exists, even a shape-neutral perspective is unlikely to change the pattern. Taking the game’s lessons to their conclusion, for racially segregated institutions and neighborhoods to integrate, a neutral stance would not be effective. The individual decisionmakers would need to both prefer diversity and eschew being in the overwhelming majority.

Changing individuals’ preferences for diversity may seem like a tall order, but a 2015 Urban Land Institute survey shows that not to be true. Sixty-six percent of Americans expressed a preference to live in “a diverse community where people are from different cultures and backgrounds” as opposed to one in which “people are mostly from a similar culture and background.” When the responses were broken down by generation, the shift in attitudes is clear. While just 44 percent of the war/silent generation could be characterized as diversity seeking, 61 percent of baby boomers, 72 percent of Gen Xers, and 76 percent of millennials expressed a preference for diversity.

Analysis of the 2010–14 General Social Survey, however, shows that a growing preference for diverse communities does not equate with progress toward reducing racism against blacks. White millennials expressed racial prejudices about blacks’ work effort and intelligence in similar shares as white Gen Xers and baby boomers, although both Gen Xers and millennials were less likely than older generations to oppose living in a 50 percent black neighborhood. Perhaps attitudes toward race, as with many topics, are becoming more starkly divided, with moderates or people who might previously have remained silent beginning to take a stand.

Pathways to More Equitable Alternatives

While there is still much to understand about individual attitudes that contribute to segregation, one thing is clear: doing nothing will get society nowhere. The federal government, through the Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing rule and the Supreme Court’s disparate impact ruling, has affirmed this. The federal government is using the power of the purse and the legal system to remove incentives for activities that fail to create more equitable and integrated communities or contribute—even inadvertently—to differential outcomes by race or other protected class.

Applying that will take not just individual actors, but an array of societal systems, including a substantial role for planners.

Public participation is central to planning, yet the array of voices that participate is rarely representative of the community. The typical meeting style, length, and time attract the most vehement advocates and opponents. Often excluded are working families overwhelmed by obligations and people who believe their voices will not be valued. Unspoken rules about the ownership of community spaces can lead to imbalanced perspectives as well. This is especially true in gentrifying areas where public meetings can be dominated by newcomers asserting their perspective without recognizing cultural context or by long-standing residents skeptical of the changes they see and anticipate around them.

New methods of community engagement can help planners hear from more members of the community, obtain feedback from underserved populations, and layer deeper observations along with the broader range of voices. In her work to reenvision a former industrial site in the low-income Bayview/Hunter’s Point section of San Francisco, architect Liz Ogbu partnered with StoryCorps to capture oral histories from area residents. Ogbu also used the site to host a circus and communitywide cookout to bring all the local voices, including youth, to the table and understand what they value in the community and what they think it needs.

Even with a participatory process, effective solutions for racial integration or for improving housing access or community resources for underserved populations often go unmet because of regulatory, policy, or financial barriers. Modernizing zoning and planning processes can facilitate a healthy housing market with a range of development types, including accessory dwellings, rental housing, subsidized housing, and multifamily. Allowing greater residential density in the suburbs might begin the process of racial integration, but there are still more opportunities to improve equitable access. Federal rental assistance shortfalls, which leave one in four eligible households trying to make ends meet without housing assistance, make affordable options for extremely low income households unlikely. Census poverty figures document that the exclusion of poor households will have a disparate impact on blacks and Hispanics.

Finally, the world of housing finance can look inward to assess opportunities for furthering economically and racially integrated communities. Housing and community developers struggle to access sufficient financial resources to support the development of affordable housing at the scale needed, to add services that may save social costs in the long run, or to deliver a slightly different housing model, such as modular development or even a mixed-income property in a non-hot market. In some cases, change may require federal action, such as an expansion of the Low Income Housing Tax Credit, but there might also be ways for other institutions to make progress within the constraints of existing resources. Philanthropic investments have supported preservation of affordable rental housing, and innovative programs by the Connecticut Housing Finance Agency are filling a finance gap for small multifamily properties. Other entities can likewise identify where their strengths can fill a gap for affordability and racial integration.

To make meaningful progress on equity, it is not enough to write laws that prevent the intentional creation of separate and unequal institutions, such as the Farmville schools of 1951. Brown v. Board of Education was decided more than 50 years ago, yet school segregation abounds. The Fair Housing Act has long been the law of the land, yet housing discrimination continues. Meaningful change can occur with a concerted and long-term effort by public, nonprofit, philanthropic, and private-sector actors, from local communities to the White House and Congress—all focused on creating an equitable and inclusive land of opportunity.