Robust Eviction Data Can Keep Cities from “Designing Policy in the Dark”

The threat of eviction is nothing new for the millions of families who have been forced out of their homes, potentially leaving their neighborhoods, schools, and support systems behind. But what is new is city leaders’ recent focus on lowering their eviction rates, largely because of a growing body of national data. Research has heightened the focus on identifying solutions to prevent this shock to a family’s sense of stability.

"Eviction is a giant problem that we only know is giant because of being in touch with communities.” Matthew Desmond, founder of the Eviction Lab and professor of Sociology at Princeton University

Matthew Desmond, author of Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City and founder of the Eviction Lab, has spearheaded the effort to bring more data and insight into the causes and consequences of evictions. The Eviction Lab published the first national dataset of evictions earlier this year, drawing on 83 million eviction records dating back to 2000.

Desmond said the inspiration for the database came from traveling to communities across the US and being repeatedly asked what the eviction rate was in those specific cities. But he couldn’t answer those questions without national data.

“Eviction is a giant problem that we only know is giant because of being in touch with communities. But we had no national eviction database. That’s akin to not knowing how many car accidents or cancer cases there are each year,” he said. “It’s important to know what cities have the highest and lowest eviction rates and to learn what’s working. We’ve been designing policy in the dark.”

Despite this increased attention, policy analysts still struggle to find complete answers about many aspects of the eviction crisis. What is the cost of eviction, and how does it compare with the cost of prevention? Where do families go after being evicted? Who are the most common evictors in each city, and what would bring them to the table for solutions? The answers to these questions, among countless others, can improve policy solutions for all aspects of formal and informal eviction.

After a breakthrough in eviction data, we still don’t have all the answers

The Eviction Lab’s database has cleaned and aggregated individual records from eviction cases. This information is used by tenant screening companies but was previously available to policy researchers, as the best available data were expensive to obtain at scale or were available only in annual court reports for counties or regions.

There are so many things short of formal eviction that are, in essence, still eviction.”Brett Theodos, principal research associate at the Urban Institute

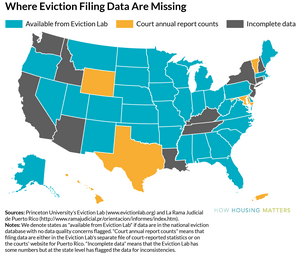

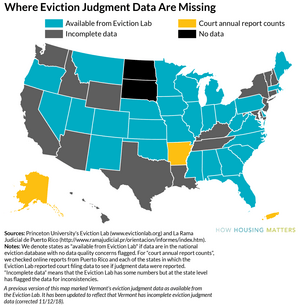

Despite the Eviction Lab’s advances, the database lacks data for several states that seal their eviction records, have incomplete records, or don’t release their records publicly. Desmond acknowledges the holes in his database and hopes that releasing the data publicly sparks a conversation and encourages researchers and officials in areas with limited data to help fill in the gaps.

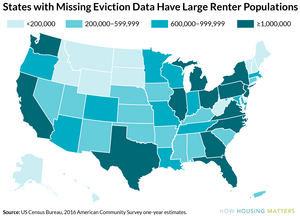

Many states have missing or incomplete data for both eviction filings, when a landlord files a notice against the tenant, and eviction judgments, when a judge decides whether the tenant must leave. Eleven states have incomplete data on eviction filings, and 17 states lack complete data on eviction judgments, hampering effective policymaking in those areas. Additional states, plus the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico, offer only aggregated counts through annual court reports.

Data are missing from states with some of the highest renter populations, such as New York and Texas. Without this information, a national picture of eviction isn’t possible.

Data gaps are sometimes in states, like California, that seal records of eviction filings to protect renters. Researchers hope to strike a balance with states to allow access to these records and boost evidence around evictions while ensuring that sealed records remain secure so tenants keep their information private and so landlords can’t use that information against potential renters.

The benefits of better legal data

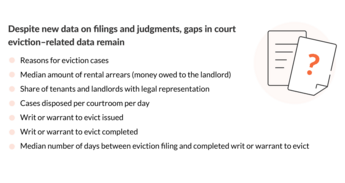

Filings and judgments are just two pieces of official court data related to the eviction process. We don’t know much about other steps of the process, such as how much money evicted renters typically owe to their landlords and how long it takes to carry out an eviction case. The answers could inform the design and budget for effective eviction prevention programs.

“Data is only as good as our ability to track things and pull information out,” said Beth Harrison, supervising attorney of the Legal Aid Society of the District of Columbia. “[In DC], we know from the court how many cases are filed, and we know how those cases end. But what we don’t know from the court is how many tenants have a writ of restitution (the order that starts the eviction process) or in how many of those cases the tenant is actually evicted.”

Beyond eviction filing and judgment data, a major barrier to effectively finding solutions is the variation between jurisdictions’ legal contexts and definitions regarding evictions and legal actions. The eviction process in one city can differ dramatically from the process in another, leading to different intervention opportunities.

Desmond also wants to expand research into who the top evictors are in a city. “We know a lot about the people who get evicted. We know far less about the people doing the eviction,” Desmond said. “There’s this asymmetric information problem in the data space where we have most information about vulnerable people and very limited information about people who are often participating in that vulnerability.”

Information gaps beyond the court system

An eviction filing is just one legal step that shows up in legal records. The Eviction Lab database and states’ court eviction records don’t capture informal forced moves. Many families move out when they receive a notice from a landlord, rather than fight in court to keep their housing. That leads to forced moves that do not appear in the judgment count. Other forced moves can happen before a case is ever filed.

Data has impact. It can lead to real solutions.”Mary Cunningham, vice president for metropolitan housing and communities policy at the Urban Institute

“There are so many things short of formal eviction that are, in essence, still eviction. You might move out at the point you’re told to move out by your landlord,” said Brett Theodos, a principal research associate at the Urban Institute. “Eviction is one very formal step, but there are lots of steps that look a lot like eviction that are just short of it.”

Harrison said she wants to know where people who have been evicted go afterward. Are they leaving DC because of a lack of affordable housing options? “If they’re staying in the District, many are probably moving to poorer, more segregated, less service-rich neighborhoods. But we don’t fully know the answer to where they’re going after an eviction,” she said.

To help fill this evidence gap, Desmond has worked with the US Department of Housing and Urban Development’s American Housing Survey (AHS) to add a question into the next iteration of the survey about informal evictions. Those results will be included in the next published AHS.

Another barrier is the lack of research around the causes and consequences of evictions. A family’s path after eviction is still a gray area, and the true cost of eviction hasn’t been fully explored. The evidence around these choices and the paths from one decision to another are lacking, and researchers have called for further study of all stages of residential instability.

Several questions remain about who eviction affects and how it affects them, such as how eviction rates vary by race or ethnicity, gender, family status, and disability and whether the evicted renters have a housing subsidy, a prior eviction judgment on their record, or other instabilities such as a job loss. And there is one big question that could have major implications for all research into evictions: Where do evicted renters go after their eviction, and what instabilities do they face in the days and months afterward?

How data can drive the next steps in solving the eviction crisis

Filling in these research gaps can lead to stronger eviction interventions, but the large number of unanswered questions shouldn’t get in the way of policy progress.

These are the conversations people deep in this work have all the time, but it’s not always at the forefront of policy discussions among elected representatives.”Beth Harrison, supervising attorney of the Legal Aid Society of the District of Columbia

City leaders and local organizations can use the Eviction Lab data as a conversation starter and a jumping-off point to dig deeper into the data for their area, said Leah Hendey, a senior research associate at the Urban Institute and codirector of the National Neighborhood Indicators Partnership. She also encouraged cities to share what has worked and what hasn’t in their efforts to keep residents from getting evicted.

Some cities have implemented measures to help renters facing eviction, such as New York City and San Francisco, but it will take time to see how these efforts affect eviction rates.

Mary Cunningham, vice president for metropolitan housing and communities policy at the Urban Institute, noted that these steps are promising as cities figure out what solutions help their residents. “Data has impact,” she said. “It can lead to real solutions.”

Harris is optimistic the recent spotlight on evictions will bridge the divide between conversations around eviction and broader conversations around housing affordability. “Desmond’s work has the potential to spark those discussions about how cities and states could adopt policies to prevent eviction and meet affordable housing needs,” she said. “These are the conversations people deep in this work have all the time, but it’s not always at the forefront of policy discussions among elected representatives.”

Maya Brennan, Kimberly Burrowes, Alice Feng, Veronica Gaitán, David Hinson, Ally Livingston, Brittney Spinner, and Jerry Ta of the Urban Institute contributed to this feature.