Merging Schools, Improving Equity: Inside a Chicago Community’s Effort to Dismantle a Pattern of Segregation

By Emily Peiffer and Anna-Lisa Castle

Chicago is starkly segregated by race and income. But the city’s schools are even more segregated than its neighborhoods, and school segregation persists even in more residentially integrated areas. For students, this can perpetuate vast disparities in education resources and hinder children’s opportunities and well-being.

This disparity was clear in Chicago’s Near North neighborhood, where two public schools sat just one mile apart but looked very different. Ogden International School, in the city’s wealthy Gold Coast neighborhood, served a largely affluent and ethnically diverse—but plurality white—student body. At the neighboring Jenner Academy of the Arts, located where the Cabrini-Green public housing complex once stood, nearly every student was black and from a low-income household.

The schools also faced opposite challenges: Ogden was overenrolled and Jenner was underenrolled. Ogden attracted students with its prestigious K–12 International Baccalaureate curriculum, but overcrowding strained its facilities. And, like many other Chicago public schools educating low-income students of color, Jenner’s low enrollment numbers meant the school received less aggregate funding under the student-based budgeting model used by Chicago Public Schools (CPS), which affects the resources the school could provide for its students.

Merging the two schools could offer a clear remedy for both schools’ problems, especially given their proximity. But this effort was unique; instead of a mandate from the district, the push to merge came from the community—including parents, students, local faith leaders, philanthropists, and school administrators.

After years of parent and community organizing, CPS approved the plan for a merger in 2017. On September 4, 2018, the merged school opened.

Reverend Randall Blakey of LaSalle Street Church, executive director of the Near North Unity Program and a leader of the merger effort, said that even though the schools’ enrollment concerns were a driving force behind the merger push, proponents had bigger goals in mind.

“We saw the overcrowding at Ogden and the underenrollment at Jenner as an opportunity to create a cross-cultural learning experience that had never been experienced in this neighborhood or in Chicago public schools before,” he said. “This could become a model not only for our city but also for the country—bringing people of different backgrounds together to help them learn together.”

How neighborhood change left a school behind

Improving educational outcomes and reducing segregation could improve economic and racial inclusion in Chicago—which currently ranks in the bottom 25 percent of US cities for overall inclusion—and could create more equitable opportunities as today’s students grow into adulthood. But patterns of housing discrimination, segregation, and displacement can compound neighborhood inequities, including in education. And even though residential integration can enable more inclusion in schools, other factors in school systems and parental choices can keep students apart.

Jenner is an excellent example. The school primarily served children living in the Cabrini-Green area, named for the public housing complex that once housed more than 3,600 households before many of the apartments and townhomes became vacant because of disrepair.

The current Jenner building was built in 2000, around the time when the city’s public housing authority was tearing down most of the complex’s buildings. Though each of the 1,770 households displaced from Cabrini-Green during redevelopment has a right of return, many have either missed out on the opportunity to return or have chosen not to do so.

The new buildings in the Cabrini-Green area serve a mix of income groups, with some homes carrying deep subsidies that former residents need, others carrying lighter rent subsidies, and many adding market-rate housing in the neighborhood.

Many families who moved into the neighborhood’s market-rate housing avoided sending their kids to Jenner, according to Scott Goldstein, principal at Teska Associates, who helped develop the Near North Quality of Life Plan in 2015. Parents of greater means had more opportunities to send their kids to private schools or to use the city’s school choice system to apply to higher-performing schools in other parts of the city, he said, because they had more time, resources, and social connections to find other options.

As a result, Jenner’s attendance dropped in the years after Cabrini-Green’s buildings came down, which meant it received less overall funding from the school district. Schools in the US with mostly low-income students and students of color are more likely to employ teachers with less training, offer a less rigorous education, and have inadequate facilities. The merger aimed to improve Jenner students’ access to the benefits of a well-funded education.

“Those students [at Jenner] have never been able to benefit from the large amounts of money poured into other schools for education in the surrounding area. [This merger] would reduce the racial achievement gaps across the board,” Blakey said.

The merger also presented the opportunity to combine student bodies from different racial and socioeconomic backgrounds. For students of color, school integration—which peaked in the US in the late 1980s and has since fallen—often means greater access to well-resourced classrooms, smaller class sizes, and increased per pupil spending. This can have long-term benefits for these students, including improved health, job prospects, and earnings potential. And desegregation can result in all students being better prepared for the workforce.

“You’d be producing a higher quality of student—a student more empathetic and amenable to working with folks that didn’t look exactly like them,” Blakey said. “It would help to reduce the racial biases and stereotypes that a number of these students would grow up learning and embracing if this didn’t take place.”

Cultivating a community-driven effort

Conversations around the potential merger of Ogden and Jenner started years before it was approved, with local faith leaders and school administrators discussing the idea as a far-off possibility. Those early talks focused on community involvement and the importance of ensuring that the people affected by the change—those in the two nearby yet distinct communities—would be central to the process.

In 2016, the Jenner-Ogden Community Steering Committee was formed. The committee leaders, Blakey and Rabbi Seth Limmer, attended every school board meeting between 2015 and 2018 to update the board on their progress. “We immediately established the face of the Jenner-Ogden Steering Committee as myself, a black pastor, and Rabbi Seth Limmer, a white rabbi of the Sinai Congregation,” Blakey said. “If we were going to do this, the optics needed to be aligned with the goal we were trying to achieve.”

The steering committee worked with CPS and members of the Chicago school board to shape the merger plan. Blakey said the president of the Chicago school board told him the merger push needed two main elements to be successful: “It had to be a community-driven effort, and [we had] to be knowledgeable of and able to respond to all reasonable opposition.”

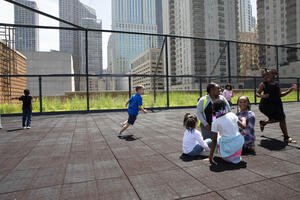

In addition to local faith leaders, the steering committee worked with students, parents, and administrators from both schools. It also held community events for families from Ogden and Jenner to give them a chance to get to know each other and understand their shared goals.

In 2016, the committee received a grant from The Chicago Community Trust to hire a consultant who examined enrollment projections, conducted family interviews, and analyzed evidence around school integration. The consultant produced a report and provided recommendations that supported the merger between the two schools.

Cheryl Nevins, portfolio planner in CPS’s Office of Demographics and Planning, said the consultant’s report played a big role in the school district’s decision to approve the merger. “The community organizing, generating a steering committee, and generating the report pushed the proposal to the forefront. It said to the district, ‘We have thought about this, this is intentional, and together we are proposing this,’” she said.

Merger efforts faced opposition from some parents, mostly those from Ogden, who expressed concern about the merger negatively affecting their kids’ educational experience. “There were racial over- and undertones that we had to deal with,” Blakey said.

Proponents of the merger cited research showing that integration doesn’t have a negative effect on white students’ test scores. Other parents were worried about sending their kids to school in the area around Jenner because of expectations of higher crime. But steering committee representatives pointed to the section of the consultant’s report on crime statistics, which showed more crimes were, in fact, reported near Ogden than near Jenner.

Despite the committee’s efforts to quell all parents’ concerns, some Jenner families were wary of the merger, and some Ogden families chose to find another school for their children. But those families who chose to leave were in the minority, as the merger had broad support among families in both schools, according to the report.

In mid-2017, after years of planning and organizing, CPS approved the Ogden-Jenner merger for the 2018–19 school year.

Ensuring all students feel at home in the new school

On September 4, 2018, the merged school opened its doors as Ogden International School. Students in grades K–4 attend the East Campus (formerly Ogden Elementary), students in grades 5–8 attend the Jenner Campus (formerly Jenner Elementary), and students in grades 9–12 attend the West Campus (also known as Ogden International High School). All students who live in the neighborhood school’s boundaries now have access to its International Baccalaureate program.

CPS funded efforts to make the transition easier, including training Jenner faculty to teach the International Baccalaureate program curriculum, but the first year as a merged school still came with challenges.

The school faced a lack of stability in leadership, as Robert Croston, the principal of Jenner, died of complications related to a genetic disease in March 2018—after CPS approved the merger but before he could see the new school open. In November 2018, just a few months after the merged school opened, CPS removed Ogden principal Michael Beyer from his position amid claims he falsified attendance records during previous school years. And Rebecca Bancroft, who served as the acting principal after Beyer’s removal, left her position at the end of the first school year.

The merger also brought the challenge of maintaining Jenner’s identity, as the new school was simply called Ogden International. Some Jenner parents have also expressed concerns that they and their children don’t have an equal voice in the school and that treatment isn’t equal for all students, as black students were disciplined more frequently than other students in the first year as a merged school.

To address these and other challenges, the school plans to invest in more counselors, diversity and inclusion training, parent feedback interviews, and communications staff, according to Blakey.

Cara Kranz, head of Ogden’s East Campus, said school officials aimed to make each campus somewhere that students from Jenner and Ogden would feel at home. They hung up artwork from both former schools in each building and had familiar teachers greet the students as they entered the new schools.

“It wasn’t about conforming to a new culture. It was about valuing what was before and keeping those things that were valued and finding a way to work together,” Kranz said. “I’ve seen over the course of this school year those lines of where we went to school before no longer dividing us. They’re blurry; they’re not at the forefront of any conversation.”

The merger also showed connections in the schools’ brands and values. Under Croston, Jenner emphasized the importance of “N.E.S.T.: Be Neighborly. Stay Engaged. Be Scholarly. Use Teamwork.” The philosophy was featured everywhere, from Jenner’s walls to its students’ uniforms. At Ogden, the school’s mascot was the owl, which lent itself to easily combine with the Jenner nest. “I like to think it was fate to have the nest and owls come together,” Kranz said. “Now we have an owls’ nest.”

Drawing lessons from one school’s experiment

After just one year as a unified school, it’s difficult to measure the success of the merger. School officials, parents, and community organizers are waiting for the results of the latest test scores to see the academic results of the first year, but they also note that test scores aren’t the only metric of a school’s success.

“We are giving equitable access to a high-quality academic program such as an [International Baccalaureate] learning experience,” Kranz said. “The value that we have from learning from one another is what makes us strong. Students who live so close to one another in terms of proximity in a city can have such different daily experiences. When they connect and share and broaden each other’s perspective, they add value to each other’s lives.”

The keys to getting the Ogden-Jenner merger approved included the community-driven approach, support from the schools’ principals, collaboration with the district, and evidence to back up claims regarding the merger's potential effects on students, according to Blakey.

Goldstein said mergers are just one potential way to address school segregation challenges. Other tactics include adjusting school funding formulas, redrawing school attendance boundaries to make schools more racially inclusive, and leveraging the evidence base that shows the connection between residential and school segregation.

Proponents of the Ogden-Jenner merger hope their experience can serve as a model for other communities who are grappling with stark educational disparities and who want to promote more integrated education opportunities for all students. Creating more racially diverse and inclusive schools can expand students’ access to opportunities in their schools and in their communities, and it can show a different and more equitable path forward for communities overall.

Blakey said the merger steering committee often uses a quote from Thurgood Marshall’s dissent in Milliken v. Bradley, the case that effectively began the Supreme Court’s pivot away from school integration efforts: “Unless our children begin to learn together, there is little hope that our people will ever begin to live together.”

Anna-Lisa Castle is a policy analyst and writer based in Chicago, where she works for the Alliance for the Great Lakes and is pursuing her master's in public policy and administration at Northwestern University.

Maya Brennan and Kimberly Burrowes of the Urban Institute contributed to this feature.