High-Return Investments for America’s Children

by Maya Brennan and Erika Poethig

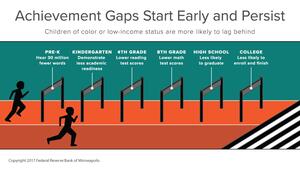

Since the Federal Reserve System hosted the first Community Development Research Conference 20 years ago, more than 10 million Americans have dropped out of high school and far too many children have missed out on high-quality learning experiences during their foundational years. These missed opportunities affect children in question and lead to high social costs, including fewer skilled workers over time. Presentations at last month’s conference showed how much we know and still need to learn about what matters for children’s success. The challenge now is how to move beyond small-scale success stories to effect national-level change.

The nation’s children are on parallel tracks based on their parents’ income, according to research presented by Katherine Magnuson of the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Children born to lower-income parents are less likely to attend preschool than children in middle- or higher-income households. This carries over into gaps in both test scores and college graduation rates. Though studies have found particularly high-quality preschools can yield a full year’s worth of improvement for young children, attending even an average preschool gives kids a cognitive boost.

This is because the brain is in such as a rapid state of development from the prenatal period to age 5. The capacity to focus, plan, and follow instructions gets its foundation during this preschool period, and then the brain gets another bump as factors like risk-reward assessments improve between ages 15 and 25. Supports and guidance can help children build these life skills at the most opportune times. Or economic hardship, neglect, abuse, exposure to violence, and other adverse experiences can hinder healthy brain development.

Reduce Educational Gaps by Reducing Housing Disparities

A foundation of good housing in childhood allows good things to happen. For low-income families, housing that is affordable allows families to support their children’s development. As Sandra Newman presented, child-enrichment spending is higher among low-income families spending around 30 percent of income on housing than those spending much more or less. In another study, Amy Schwartz found that low-income children’s test scores go up if their family gets a housing voucher. Stronger improvements in achievement for low-income students can occur with residential integration, such as occurs with inclusionary zoning policies, according to research by Heather Schwartz.

With housing deficiencies come poor outcomes. This includes missed opportunities for child-enrichment activities and supportive school environments and direct harms from housing-related hazards and stress. For example, economic distress in the home or neighborhood is connected with increased reports of child maltreatment.

The housing challenges that affect children’s development and schooling are widespread. According to The State of the Nation’s Housing 2016, difficulty affording housing is a nearly universal experience among the nation’s lowest-income households, and 72 percent of lowest-income renter households spent half of their income to maintain housing. In 2014, low-income households with severe housing cost burden had just $500 left to cover everything else for the month, leading to reductions in spending on food and health care, which in turn affect children’s readiness to learn.

Further inequities exist by race and ethnicity. The layering of residential segregation and disinvestment patterns contributed to a greater likelihood for children from black or Hispanic families of any income level to live in very low opportunity neighborhoods, as rated by the Child Opportunity Index.

As Joanna Taylor, Tatjana Meschede, and Alexis Mann of Brandeis University presented, race is linked with whether a family can live in their preferred school district and whether they need to trade longer-term asset growth and stability to do so. In the Leveraging Mobility Study performed by Brandeis University, nearly all of the white families could buy a home of some sort in their desired school district, but black families in the study were rarely able to live in the school district they wanted for their children. In the exceptions, black families prioritized their children’s education at the expense of their own assets, opting to rent instead of own a home or fully cashing out retirement savings to buy in the desirable district.

A Crisis or a High-Return Opportunity?

One can view the nation’s longstanding achievement gaps, employment gaps, and housing challenges as a crisis to tackle with “overwhelming force” or as a missed opportunity for high-return investments in children’s futures. Either way, experts at the event agreed that the current pace of change is too slow.

Making nationwide progress more quickly requires a willingness to push hard on multiple fronts—raising expectations for results, ensuring greater accountability, and identifying the public, private, or philanthropic partners sufficiently aligned with the mission to fund the work at the level needed. Early childhood education used to operate with a siege mentality, where the field seemed to think it too risky to ask questions about program quality in case decisionmakers used weaknesses in the results to cut program budgets rather than seeking opportunities for improvement, according to Jack Shonkoff of the Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University. As the evidence base has grown, the field has grown more confident that programs can achieve the standards of evidence-based policymaking. Shonkoff still stressed the importance of also looking beyond statistical significance as the end goal and in seeking to understand and apply lessons from the highly effective outliers.

The case for funding is stronger with evidence of a return on investment (ROI) and a role for market-based actors. Arthur Rolnick of the University of Minnesota presented a model for high-ROI early child development that includes a combination of home-visiting and partial to full early education scholarships for low-income families with young children. The model, which started in St. Paul, MN, allows parents to use their scholarship at any highly rated provider, creating a market for high-quality early education in low-income communities. When providers in the Twin Cities area learned that low-income families in St. Paul now had capacity to pay for early learning programs (but only if the programs met quality standards), the number of highly rated early education programs in the city’s low-income neighborhoods rose 85 percent. With (funded) demand, the supply came.

And the funding came thanks to extensive evidence of the public ROI in early education. To improve the case, Rolnick and others have calculated the program’s internal rate of return, rather than just showing costs and benefits. This approach could pave the way for even greater investments.

The budgets for housing assistance, gap financing to keep rents down, and other supports are thin and regularly get thinner. The siege mentality that Shonkoff described in early education is already apparent in housing, but holding the line would be a weak victory. With more than 19 million children in the United States at risk of falling behind in development and academics because their family is low income and cost burdened, it is time for the nation to adopt a more complete housing solution.

The education and early child development systems cannot be forced to tackle the nation’s achievement gaps on their own while gaps in housing access undermine the education field’s hard-fought gains. To yield better outcomes 20 years from now, the nation needs to change its course on housing. The solution could build on the structure already in place or start anew. It just has to be big enough to match the scope of the challenges facing America’s children, their caregivers, and the communities in which they live.

Videos, presentations, and other material from the 2017 Federal Reserve System Community Development Research Conference can be accessed on the conference website.