What Gets Lost in the Definition of Inadequate Housing?

Photography by Maura Friedman and writing by Emily Peiffer, Maya Brennan, and Kimberly Burrowes

Although people who live or work in low-income communities regularly see serious housing quality problems, major national reports often find that the amount of inadequate housing in the United States is low. Just 1.3 percent of unassisted US households (1.5 million) lived in severely inadequate housing in 2015, according to calculations in the most recent Worst Case Housing Needs report to Congress.

One reason for this low number: the definition of worst case housing needs, as directed by Congress decades ago, leaves a lot to be desired.

The worst case needs definition only incorporates the types of housing inadequacies that indicate an unsound structure—not the types of quality problems that pose an imminent risk to residents' health and safety.

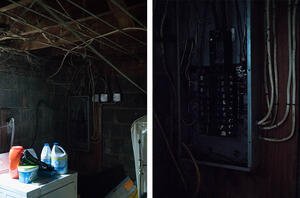

Housing is designated as having severe or moderate physical problems through a combination of indicators collected in the American Housing Survey (AHS). These physical inadequacies relate to plumbing, heating, electricity, and upkeep, and they range from lacking a flushable toilet to having no electricity. But many problems that most people and code enforcement officials would deem serious—such as holes in the floor or several blown fuses in the past few months—wouldn’t be considered severe under the AHS definition of adequacy. These health and safety hazards lead to a classification of “severely inadequate” only when they occur in combination with multiple other hazards.

This focus on combinations of problems causes the national housing quality debate to miss many known health and safety issues. Living in substandard housing takes a toll on residents’ physical health and mental health, and it can have ripple effects for children’s development and education. Despite data collection on many home hazards, the combined statistics on inadequacy do not deliver the information we need on how many people live in unhealthy housing. The aggregated approach also means only the most highly specialized decisionmakers know the prevalence of specific, solvable problems. Without a detailed understanding of substandard housing conditions, how can we direct funding and policy attention to the right areas?

The photos below show some of the housing hazards that, if they occurred without any other designated problems, would get lost in the current definition of inadequate housing.

Rebuilding Together contributed to this feature by connecting us with homeowners facing housing quality challenges in Northern Virginia. Their volunteers have since corrected these hazards.