(ungvar/Shutterstock)

Five Housing Issues Motivating Young Voters

Millennials and Generation Z make up more than 40 percent of the US population and an increasing share of the electorate, projected to represent the majority of all voters within the next five years. Recent polls show housing is a major factor in how young people plan to vote in the coming presidential election.

This is likely because housing has become less and less affordable over their lifetimes. The cost of housing has risen significantly, with home prices up by more than 54 percent since 2019, and they don’t look to be dropping, given limited housing supply and today’s high interest rates. And renting is more expensive, with rents increasing by more than 30 percent since 2019, outpacing wage gains, leaving renters with diminished ability to save for homeownership. As they’ve entered their prime homebuying years, homeownership looks to be an unattainable dream. And this is reflected in reality: young adults today are less likely than their parents were to be homeowners.

Without becoming homeowners, young peoples’ chances of building significant wealth over their lifetimes is greatly diminished. Not only does this pose concerns for young people, but this also bodes poorly for the financial future of the country, as a greater generational wealth divide could severely limit the country’s overall economic growth and stability.

We offer data on five housing trends from recent analyses and their implications to help policymakers determine which policy levers to pull to make homeownership more attainable for young people.

1. Homeownership continues to be the primary wealth-building mechanism in the US. But barriers to homebuying for young people are widening the wealth gap across generations.

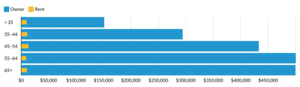

Homeownership remains a key source of wealth building in the US. The most recent data from the Survey of Consumer Finances show that median wealth increases with age for homeowners until postretirement age, while renters’ median wealth doesn’t vary much with age. Instead, as the typical homeowner gains thousands of dollars as they get older, the median wealth of renters stays around $9,000 to $13,000 for all age groups, resulting in a greater wealth gap between renters and owners for older populations.

Our study finds those who bought their homes earlier in life have substantially higher housing wealth in their 60s. This indicates the current challenges young adults are experiencing in obtaining homeownership can have long-term consequences for their wealth.

The Median Wealth Gap between Homeowners and Renters Increases with Age

Median wealth by age

Source: 2022 Survey of Consumer Finances.

2. The wealth gap has increased between young renters and young homeowners, and disparities in inheritances—paired with high home prices—have created disparities in who can buy homes.

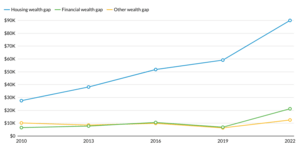

Among young adults, we’ve observed greater wealth disparities between homeowners and renters in the past 10 years, and housing has been the major driver of the growing gaps.

In the Past 10 Years, the Wealth Gap between Young Homeowners and Renters Has Increased

Wealth gap for those 35-years-old and younger

Source: Survey of Consumer Finances.

Notes: Wealth is adjusted to 2022 dollars using the Consumer Price Index. Adding the median wealth gap for the three categories is smaller than the overall median wealth gap because of the distribution of the three wealth categories. Financial and other wealth, which includes business assets, nonresidential real estate assets, and other types of assets such as automobiles, are significantly skewed toward the upper end of the distribution, especially for homeowners. Housing wealth is also skewed toward the upper end of the distribution but to a lesser extent.

As wealth transfers from generation to generation, we may see more wealth inequality between children of homeowning parents and children of renting parents as their parents start to downsize after retirement and support their children. A recent survey finds 36 percent of young adults are planning to receive cash from their families to fund a down payment, double the share in 2019. This raises significant concerns for equity and economic security more broadly.

The US population is becoming more and more diverse. According to US Census Bureau data, in 2022, the white population accounts for 71 percent of all people ages 55 and older, but fewer than half of those younger 35. Our research finds that in the next 20 years, all net new homeowners will be people of color, while the total number of white homeowners will decline. And young people of color make up nearly half of newly eligible voters in the 2024 election, even more in southern and western states.

For young adults of color, who are less likely to have wealthy, homeowning parents, partly because of historical racial discrimination in the housing market, this means homeownership is further out of reach. However, the current housing finance systems don’t serve the needs of the growing share of young adults of color struggling to access homeownership.

3. Lack of housing supply is a primary barrier to young adult homeownership.

Housing prices have grown significantly in the past decade partly because of a severe shortage of affordable supply. Though estimates of the shortage vary, they range from 1.5 to 5.5 million units short of what’s needed. This shortage stems from two trends:

- There are fewer existing homes for sale on the market today than in previous years, in part because homeowners locked into low mortgage rates don’t wish to trade in that rate for today’s rates, which are close to an all-time high. Even people who bought “starter homes” in the past few years who may have, under typical housing market conditions, gone back on the market to find a larger home in a different location, are finding it hard to upgrade, meaning there are fewer homes for sale for first-time homebuyers.

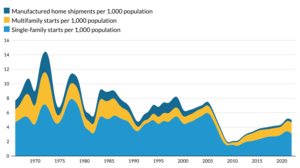

- The shortage reflects that, controlling for population, homebuilding is down significantly from the level it was at for decades leading up to the Great Recession. When the parents of millennials and Gen Z households were in their prime homebuying years, the number of homes on the market, particularly at the more affordable end of the distribution, was significantly greater than it is today.

Population-Adjusted Housing Production

Sources: US Census Bureau data and Urban Institute calculations.

Note: Single family = 1–4 units.

4. Younger adults are experiencing higher debt—in part related to college costs— which is further limiting access to homeownership.

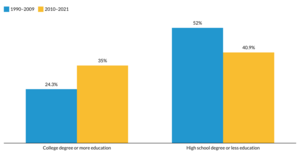

With rising returns for higher education, college enrollment has risen significantly since the 1990s, when about 13.8 million people were enrolled in undergraduate or graduate programs, compared with about 19 million people in 2023. Over this period, the share of those living with their parents past age 30 who have a college degree or more education has increased significantly while the share of those living at home past age 30 with a high school degree or less education has decreased.

People Ages 30 and Older Who Live with Their Parents Are More Likely to Be Highly Educated Today

Share of people ages 30 and older living with parents

Source: Panel Survey of Income Dynamics, 1968–2021

Over the same period, college tuition prices have increased faster than median income. With increasing educational attainment and this shift in the real cost of education, college graduates today are taking on significantly more debt than those from previous generations.

More debt may make it even more difficult for them to save for a down payment or qualify for a mortgage. Although paying off loans on time can boost one’s credit score, if students fall behind on payments or default on their loan, that negative information can stay on their credit file for years. A period of joblessness after college—which was the case for many young people who graduated during the Great Recession and during the COVID-19 pandemic, could be a strike against young homebuyers if it affected their ability to pay off their educational loans.

All of this means increased education—and educational debt—can make it harder for young people to afford a house because debt-to-income ratios and low credit scores are linked to higher borrowing costs and mortgage application denials.

5. Climate change is also increasing the cost of homeownership and creating housing instability and inaccessibility, particularly where young people live.

This fall, policymakers have a double whammy opportunity to appeal to young voters on two of their key issues: housing and climate change. According to the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s National Risk Index and data from the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey, more than 16 percent of households headed by someone younger than 30 live in an area that’s at relatively high or very high risk for at least 1 of 18 natural hazards. And among households living in these high-risk areas, nearly 40 percent are younger than 35, even though they only make up 19 percent of total households nationwide. Based on how FEMA calculates the National Risk Index, this is likely an understatement on households exposed to vulnerability.

Climate risk is making housing more expensive through higher insurance premiums, home repair costs, disaster prevention retrofitting, and changes in construction materials. In places facing extreme heat, households have to foot the bill for higher energy costs to keep their home at a safe, cool temperature. These issues will not resolve themselves. When it comes to home insurance, the average premium rose by more than 33 percent between 2020 and 2023, with greater increases in disaster-prone areas. And these costs are projected to increase. This has serious implications for racial equity in housing, homeownership, wealth, and health.

These five points illuminate a key takeaway that often gets lost: young people are living at home for longer and are taking longer than their parents did to become homeowners, but not because they are lazy. High home prices, low housing supply, racial inequities in wealth and opportunity, increased debt, and climate change have all made it increasingly difficult for young people to access stable, secure housing and achieve homeownership. And frustrations around these issues could play a major role in the upcoming election.

How can federal policymakers alleviate housing challenges for younger generations?

- Make long-overdue changes to underwriting, particularly when it comes to metrics of “creditworthiness” that are rooted in structural racism, including incentivizing more-relaxed debt-to-income ratios and continuing to reevaluate credit scoring through a race-conscious lens, can help make what is supposed to be a neutral metric truly fair and equitable.

- Consider decreasing the impact of a late student loan payment on credit scores or decreasing the length of time such a demerit stays on one’s credit report.

- Support first-time homebuyers by providing targeted first-generation down payment assistance andpermanent mortgage rate buydowns, tax-free saving accounts for down payments, and tax credits. These steps would reduce structural racism’s influence in the housing market and mitigate the growing wealth gap between owners and renters. These supports would help young adults without parental support compete in the increasingly competitive marketplace.

- Increase the affordable housing supply (PDF). Federal policymakers can incentivize state and local governments to change land-use and zoning regulations to allow for more building, particularly multifamily homes, manufactured housing, and accessory dwelling units. And through tax incentives, policymakers can catalyze single-family home construction and rehabilitation of existing properties.

- Tie improvements in housing to improvements in climate resiliency and addressing climate change. Providing weatherization assistance, improving renovation loan structure and availability, and reconsidering cross-subsidization in the insurance market are all opportunities to support sustainable housing. Making it easier to finance and build manufactured housing—new models of which are better for the environment and equally, if not more, able to withstand natural disasters—will require federal and local efforts. Ensuring dollars and attention are targeted to younger households, primarily those of color without generational wealth, will help mitigate the effects of climate change.

The bottom line is that housing matters. It matters to young people who want to buy homes but face significant barriers in both affordability and availability, and it will play a significant role in how they vote in the next election cycle. Access to housing matters for the economy. It affects the racial wealth gap, which is a drag on the US economy; it affects homelessness rates, which costs cities and neighborhoods significantly; and it affects earnings growth and gross domestic product. It’s in everybody’s interest for policymakers to take action to improve access to affordable housing.