Federal Fair Housing Data Can Tell Us about Access to Quality Schools

by Ruth Gourevitch

As elementary school students head back to school this month, not all students will have access to the same educational opportunities. These disparities are often determined by race and place.

Because many children attend elementary schools in their own neighborhood, a child’s access to high-quality schools is dependent on where they grow up. Racial residential and school segregation, along with policies and practices that inequitably distribute resources across neighborhoods and schools, have created a system in which students of color often lack access to high-quality schools compared with white students residing in the same region.

In 2015, HUD adopted a new rule aimed at enforcing the Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing (AFFH) requirement of the federal Fair Housing Act. The AFFH rule required jurisdictions that receive federal housing or community development funding to assess racial discrimination and barriers to housing choice in their communities and make plans to improve access to opportunity. Recognizing the link between residential segregation and access to high-performing schools, HUD also asked jurisdictions to examine access to high-performing elementary schools as part of their fair housing planning process.

To help jurisdictions complete their assessments of fair housing, HUD developed a dataset that includes information on access to opportunity, including school performance. Though HUD suspended implementation of the AFFH rule earlier this year and announced plans to change the rule earlier this month, the dataset it created to help jurisdictions assess the link between education, racial discrimination, and access to opportunity remains online and available for download.

In our recent report, we analyzed these data and what they reveal about access to opportunity across place and race. We found that access to high-performing schools varies by race and ethnicity and neighborhood location, highlighting the need for place-conscious educational reforms that explicitly target racial discrimination and patterns of segregation in US metropolitan areas.

Race, ethnicity, and access to high-performing elementary schools

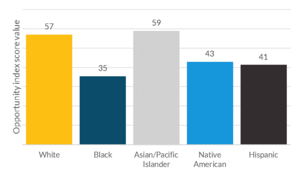

The AFFH dataset shows that black residents have the least access to high-performing elementary schools, while white and Asian/Pacific Islander residents have the most access to higher-performing schools (figure 1). Further, metropolitan areas with higher levels of black-white and Hispanic-white residential segregation tend to have larger disparities in access to high-performing elementary schools across race and ethnicity.

Meanwhile, census tracts where the majority of residents are people of color and where poverty rates are high, also have much lower access to high-performing elementary schools.

These findings highlight the unequal landscape of educational resources across regions. What’s more, areas that lack high-performing elementary schools tend to also have weaker labor markets, and more environmental health toxins. This makes upward mobility even more challenging for students growing up in these neighborhoods.

Figure 1

Exposure to high-performing schools by race and ethnicity

Local governments work to address the link between education and neighborhoods

Before the AFFH rule was suspended, 49 local jurisdictions and regions used the data to create plans to address racial segregation. Many of these plans highlighted the link between education and place as a key tenet of their future fair housing work. For example, in conducting their Assessment of Fair Housing, New Orleans cited disparities in the location of proficient schools and school assignment policies as a high priority for the city and wrote that unequal access to schools is “a major factor in [protected classes’] ability to access other opportunities.”

Despite the suspension of the federal AFFH rule, local jurisdictions continue to align their community development and racial equity plans with educational needs. The Boston Metropolitan Area Planning Council’s racial equity strategy includes a K–12 educational component, and Chicago’s “Our Equitable Future” plan recommends that educational resources be prioritized for students who reside in chronically underserved areas in the Chicago metro region.

Together, these local plans exemplify how jurisdictions, amid federal uncertainty, can work to address the inextricable link between place and education, moving toward a K–12 educational system that allows all children to access high-quality educational resources regardless of their race or ethnicity.

Photo by Wave Break Media/Shutterstock