(T-I/Shutterstock)

Do Clean Slate Laws Reduce Housing Barriers?

Many landlords screen for criminal records and disqualify prospective tenants if they have any criminal history, regardless of severity, recency, and even the outcome. But evidence shows most criminal history is not linked to rental outcomes. And on top of this, criminal history information in tenant reports can be inaccurate, incomplete, or misleading.

This leads to high barriers to housing, repeated denials (PDF), and housing insecurity for people with any arrests or convictions. And it disproportionately affects Black, Latinx, and Indigenous households, who are overrepresented in criminal legal data because of historic and ongoing structural racism that led to concentrated poverty, neighborhood disinvestment, and racism in policing and sentencing. Because criminal data lack unique person-level identifiers, these groups are also more likely to be mistakenly or incorrectly matched to criminal records in tenant-screening reports because of lower surname diversity.

Clean Slate policies seal older, more-minor, or nonconviction criminal records and have emerged as a way to reduce barriers to housing and employment for people with a criminal history. To better understand the implications of Clean Slate laws, we examined how the implementation of Pennsylvania’s Clean Slate expansion affects who is represented in the state’s criminal history data, how it affected racial representation within the dataset, and how it affected housing access.

What is Pennsylvania’s Clean Slate law?

In 2023, Pennsylvania passed H.B. 689, named Clean Slate 3.0, which did the following:

- expanded automatic sealing to include less serious drug felonies without a subsequent misdemeanor or felony conviction

- made property-related felonies eligible for sealing after 10 years

- shortened waiting periods for sealing misdemeanor convictions to 7 years and summary convictions—which are distinct charges that are less serious than misdemeanors—to 5 years

The initial Clean Slate Act was a bipartisan effort enacted in 2018. It was the first policy in the nation to automatically seal most nonviolent misdemeanor convictions (without subsequent conviction), summary convictions within 10 years, and nonconvictions within 60 days after disposition. Clean Slate 2.0 went into effect in 2020 and allowed cases to be sealed when fines and costs were still owed. The combination of these allowed for sealing of 45 million cases.

We analyzed the effects of Clean Slate 3.0 by comparing available case-level data from the Administrative Office of Pennsylvania Courts (AOPC) before and after the implementation of 3.0. Because the data have no person-level identifiers, we aggregated cases together with the same full name and date of birth. We measured the assigned racial category within the AOPC data and compared these individuals with the total number of residents within the state as reported in the 2022 5-year American Community Survey.

What are the effects of Pennsylvania’s Clean Slate 3.0 expansion?

Overall, after the implementation of the Clean Slate 3.0 expansion:

- Fewer people were captured in the data. After the expansion, 743,359 people (5.7 percent of the total Pennsylvania population) were captured in the AOPC data, compared with 895,527 people (6.9 percent of Pennsylvania’s population) before expansion, for a total reduction of 152,168 people. Although not all these individuals are Pennsylvania residents or renters, the magnitude of this drop would be equivalent to about 4.5 percent of all renters in Pennsylvania.

- Fewer offenses were captured per person. Before expansion, each person in the dataset had an average of 7 offenses, which dropped to 4.1 offenses after expansion. The number of cases on one’s record matters for housing, employment, and other opportunities that require background checks.

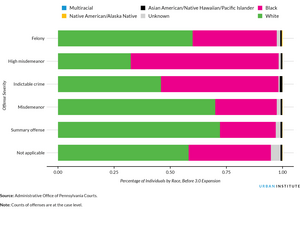

- Misdemeanors dropped the most. Misdemeanors are less serious offenses, such as petty theft, driving under the influence, vandalism, and simple assault. Misdemeanor charges dropped from 52.4 percent of all charges before expansion to 48.2 percent after expansion. Misdemeanor charges removed represent about 1.98 million charges, or 56 percent of all sealed cases. Felony charges—which are generally more-serious crimes, such as drug sales, robbery, and burglary—saw a small drop from 23.5 percent to 20.9 percent (representing about 900,000 charges).

- Summary offenses saw the smallest drop. Summary offenses are less serious than both misdemeanors and felonies and can include disorderly conduct, retail theft, or trespassing. These saw the smallest drop in charges removed (620,000). As such, the representation in AOPC increased from 21.7 percent to 27.0 percent. This is likely because of previous Clean Slate iterations in Pennsylvania, which probably affected the total number of summary offenses.

- Diverted cases dropped to 0. Diversion generally includes a defendant bypassing traditional prosecution in lieu of satisfying other conditions, such as a rehabilitation program. These are most often available to first-time offenders or those with nonviolent misdemeanor charges. Before expansion, these made up 6.0 percent of all cases.

Clean Slate 3.0 expansion didn’t reduce racial disparities in data

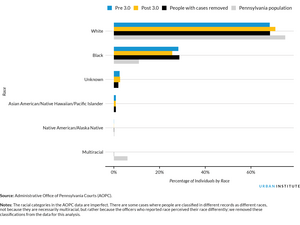

Expansion of 3.0 had little impact on the racial representation of people within the dataset. Before the expansion, Black people were disproportionately represented in AOPC data, making up about 10.9 percent of Pennsylvania’s population but nearly a third of the people in AOPC data (28.3 percent). Expansion did not affect this overrepresentation; after 3.0, Black people represented 28.7 percent of AOPC records (about 26.3 percent of people with sealed records).

Most other racial categories remained stable too. White people make up about 75.0 percent of Pennsylvania’s population, compared with only 68.0 percent of the AOPC population. Of all the individuals removed from the AOPC data, white people represented about 66.5 percent of all records sealed. The largest drop was seen by people without a racial category, who made up 3.9 percent of the AOPC records before expansion and only 2.0 percent after.

Share of People with Cases Before and After Clean Slate 3.0, by Race

Some of the racial difference in outcomes relates to the types of charges most affected. Misdemeanors, which saw the largest drop in the dataset, had the highest percentage of white individuals before expansion (72.8 percent). This speaks partly to how the felonization of drug possession disproportionately affects Black Americans, as well as the racial disparities in who gets felonies downgraded (PDF) misdemeanors.

Share of Individuals’ Offenses by Race, Before Clean Slate 3.0

There was an impact on average offenses per person by race. Average offenses were largest for Native American people, who saw an average drop of 3.9 offenses from 10 to 6.1, followed by white (drop from 7 to 4) and Black people (drop from 7.3 to 4.3).

Will renters and residents feel these effects in their daily lives?

Overall, the expansion didn’t create more racially equitable outcomes, yet it did allow for the sealing of records for more than 150,000 people who had old or minor records on their file, potentially creating new access to housing and employment opportunity.

A remaining question, however, is whether these changes will be reflected in background checks. Currently, tenant screening companies aren’t required to disclose how they maintain and update their records, but some early analysis suggests companies may not capture sealing and expungement. As a result, these policies may not translate into greater housing access.

To address this, federal and state policymakers can provide clearer guidance on data standards for tenant screening companies, monitor their data practices in ways that resemble credit reporting agencies, and reduce criminal screening’s role in tenant selection.