Assessing and Improving the Community Development Block Grant

by Brett Theodos and Christina Stacy

As the federal budget tightens, major sources of federal support for US communities are in the spotlight, but the conversations are often short on evidence—especially for block grant programs. Block grants give states or localities formula-based funding and general guidelines for their use, allowing the exact uses to be determined by the grantees, a departure from the earlier model in which federal funding rules dictated how states and localities spent funds.

For community development and housing activities, the Community Development Block Grant program (CDBG) has been a substantial source of flexible funds for more than 40 years. The program’s creation reflected a bipartisan compromise between those who wanted to devolve decisionmaking power to state and local governments and those who wanted to create a national program benefiting low-income communities. As a block grant, it could do both.

Community Development Block Grants continue to play an important role as a unique community development resource. According to the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), between 2005 and 2013, CDBG created or retained 330,546 jobs, assisted over 1.1 million people with homeownership and improvements, benefited over 33 million people nationwide through public improvements, and provided public services to over 105 million people. Furthermore, practitioners report that the program is used as the "first capital in" to a project, which is critical in attracting other capital sources.

But CDBG funding may be eliminated, and the program has faced criticism for the lack of evidence on its benefits. This lack of evidence may be more related to evaluation capacity or factors that could be addressed with different implementation guidance rather than a lack of true impacts.

What are CDBG funds used for?

Within the general categories eligible for CDBG funding (e.g., property acquisition and clearance, housing activities, economic development, public improvements and facilities, public services, and planning and administration), grantees have funded such activities as street upgrades, infrastructure infill, affordable homeownership, homeless services, and small business loans. At least 70 percent of any grantee’s funding needs to benefit low- and moderate-income (LMI) people, whether by addressing needs in an LMI neighborhood, serving LMI people directly, assisting with housing needs for this income group, or creating and retaining jobs.

For many jurisdictions, CDBG is a steady funding source dedicated to benefiting low-income people and communities, which allows them to focus on implementation rather than fundraising. The program’s flexibility allows localities to tailor solutions to their own needs and fund various activities, from providing housing loan counseling to supporting local attractions that generate economic activity.

Are these the right activities? An answer would require more guidance from HUD and other experts. Such guidance is needed and welcome. When HUD solicited feedback from grantees on program requirements, local administrators expressed a preference for more guidance on how to use funds effectively within the requirements. With support from HUD’s local field offices or other expert technical assistance providers, CDBG grantees could retain their flexibility and better understand how to use funds effectively.

How well do grantees target funds to address the needs of low-income people and neighborhoods?

The program’s inherent flexibility can raise concerns that local allocations of CDBG funding do not adequately target the needs of low-income people, but program modifications could address this. Uncertainty surrounds whether grantees adequately direct funding to LMI people. But this question focuses on rule compliance, not results. Even if funds are targeted to LMI people, the benefits may be focused at the higher end of the income range, may not address LMI people’s pressing needs, or may be spread too thin to be effective. Program modifications and greater access to expert guidance could help align grantees’ decisions with locally expressed needs and assets.

Grantees must also decide between funding social services for LMI people and brick-and-mortar development projects to improve LMI neighborhood conditions. The question of which types or mix of programs most benefit LMI people remains unanswered and may vary with local markets. Additional monitoring of funding uses and benefits would help address this. Guidelines could also strengthen income-targeting requirements, ensuring some percentage is targeted to households with income below 50 percent of the area median.

Funds may be more effective if they are more geographically concentrated, but the politics of allocating money within a city often lead to broader (and thinner) distributions. Stronger requirements for geographic targeting of funds to neighborhoods with a certain level of need could allow local officials to circumvent the politics of funding allocations and allow them to support activities at a sufficient level to have a greater impact.

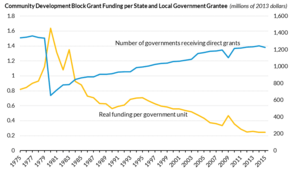

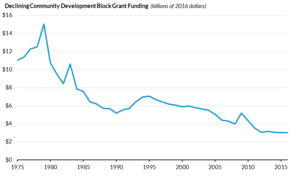

In addition, more concentrated targeting may make outcomes easier to determine, because it is hard to measure outcomes when funds are too diffuse. And for grantees, funding levels have deteriorated so much that spreading funds widely means no activity can receive much.

How can grantees and CDBG foster good performance?

Because of local fiscal stresses and the small size of each CDBG grant, some jurisdictions use CDBG as a substitute for funding gaps rather than for transformative or capacity-building investments. In addition, HUD’s ability to support, monitor, and reward grantees for good performance has diminished because of decreased staffing. Recent place-based initiatives, such as HUD’s Sustainable Communities and Promise Neighborhoods, provide examples of how higher expectations, strong technical assistance, and dedicated resources can help grantees use data to analyze their needs and create comprehensive community development strategies.

To strengthen CDBG, HUD should increase its field office capacity, reward jurisdictions for good performance, facilitate peer learning and improve technical assistance, set aside funds for planning, guide and encourage CDBG recipients to pursue public engagement, educate potential project partners about CDBG requirements, and alter regulations to encourage evidence-based practices while leaving room for risk taking and innovation. Additionally, data systems need to be improved to better monitor and reward performance.

With greater guidance from HUD, rather than elimination, the true effects of CDBG can become apparent. In reviewing CDBG, the program’s design and implementation could be reworked to allow this flexible funding source to achieve its potential as a transformative investment for distressed places and people.

Absent these changes, CDBG’s funding will likely continue its downward trend—at least in real terms—eroding this important social program and stimulus for private-sector, community-driven investment.

Brett Theodos and Christina Stacy are senior research associates at the Urban Institute. Figures and citations can be found in their report Taking Stock of the Community Development Block Grant.