Advancing an Evidence Base for Housing Laws

by Abraham Gutman

In many major US cities, renters are severely cost burdened, there is a shortage of housing for low- and middle-income households, many households live in inadequate housing, and eviction rates are high. Research examining variations in housing-related outcomes in different places often focuses on infrastructure, geography, transportation, demographics, and market pressures. The law, however, is too often neglected.

The Center for Public Health Law Research recently published three datasets that can help illuminate the role of law in housing. After all, knowing the law is the first step to evaluating it. The datasets include(1) a survey of state landlord-tenant laws spanning 50 states and the District of Columbia, (2) a survey of state fair housing laws spanning 50 states and the District of Columbia, and (3) a survey of nuisance property ordinances focusing on the country’s 40 most populated cities.

I sat down with the researchers who led each dataset to talk about what they learned.

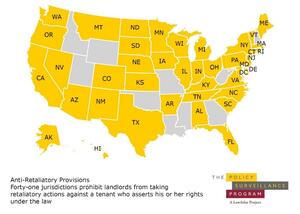

Because I’m not a lawyer, I wanted to start by understanding what these laws mean. “Landlord-tenant laws lay out the basic rights and responsibilities for both landlords and tenants when renting residential property,” explains Andrew Campbell, a program manager in the Policy Surveillance Program at the center. “[These laws] are fundamental when thinking about the landlord-tenant relationship.” Nationally, landlord-tenant laws govern the relationships between 43 million renter households and their current or prospective landlords. All 50 states and the District of Columbia have landlord-tenant laws, but the laws vary from state to state. For example, in 11 states and the District of Columbia, the law imposes a maximum security deposit equivalent to one month’s rent. Also, in 41 states, the law prohibits landlords from taking retaliatory actions against tenants who assert their rights.

To explore the state rental landlord tenant laws dataset and mapping tool, click here.

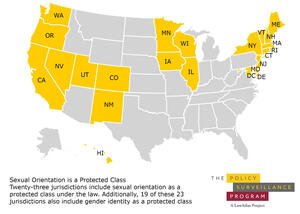

Other laws that govern relationships in housing markets are fair housing laws. In 1968, President Johnson signed into law the Fair Housing Act, which regulates discriminatory actions in housing-related transactions. “The federal Fair Housing Act is the minimum floor of protection,” explains Adrienne Ghorashi, a law and policy analyst at the center. “But state fair housing laws can vary on which protected classes are included, the different types of discriminatory actions that are prohibited, and what types of actions are exempt.” Excluding Mississippi, all states and the District of Columbia have a fair housing law. The protected classes (groups that the law protects from discrimination) in the federal law are race, color, religion, sex, disability, familial status, and national origin. “Many states include protected classes that are not included in the federal law, such as sexual orientation (23 jurisdictions) and gender identity (19 jurisdictions),” shares Ghorashi.

To explore the state fair housing laws dataset and mapping tool, click here.

Relationships between individuals are not the only housing-related relationships governed by law. Many cities have ordinances that govern the relationship between a property and the community. Katie McCabe, a law and policy analyst at the center, researched these laws in the country’s 40 most populous cities and explains, “Nuisance property ordinances are municipal laws that label some type of conduct as nuisance activity and require landlords to abate the nuisance in some way.” These laws originated as a tool for communities to respond to drug houses, but McCabe describes “concerns that these ordinances have public health implications because multiple cities (5 of the 40 cities that we studied) explicitly include calls to law enforcement, with certain exceptions in some cities, as nuisance activities. This means that tenants may be forced to either forgo calling the police or risk being penalized, possibly by being evicted.”

Research shows that over a two-year period in Milwaukee, one in three nuisance citations was issued because of domestic violence incidents. The law in Milwaukee has since been amended, and the city is one of six of those researched that exempts domestic violence–related incidents as a nuisance activity.

To explore the city nuisance property ordinances dataset and mapping tool, click here.

These datasets illuminate the ways basic housing law, not just market dynamics, can affect access, stability, and affordability. This knowledge provides essential context for comparing outcomes between places, and the researchers already have new questions that build on these datasets to improve renters’ outcomes. Ghorashi wondered “whether expanding the types of protected categories included in the law is effective at actually protecting those individuals against discrimination—should more states be doing this?” Campbell wants to consider the potential gap between the law on the books and the law in practice: “I would guess that a lot of people don’t know about the rights that they have [in the state’s landlord-tenant law].” For McCabe, the biggest question is this: “In the cities that have nuisance property ordinances, what percentage of evictions in those cities occur because of the ordinances?” Answering these questions does more than add to the evidence about housing problems. Comparisons of housing law can set a community on course for solutions.

Abraham Gutman is a senior policy and data analyst at the Center for Public Health Law Research at the Temple University Beasley School of Law, where he studies housing policies and drug laws. He holds an MA in economics from Hunter College. Follow him @abgutman.