Nason Park Manor, one of BangorHousing’s senior-specific residential buildings

From Landlords to Lifelines

How Public Housing Authorities Are Protecting Senior Residents during COVID-19

At 78 years old, Ronald Reed likes to keep busy. He owned an interior painting business for 20-odd years, but after he retired, he took up jewelry making. “It’s not the high-class silver and gold stuff,” he said, but it’s very detailed, which keeps his mind off his fibromyalgia pain. These days, stuck inside his apartment in Bangor, Maine, because of the COVID-19 pandemic, Reed has been making a lot of jewelry.

Reed moved into BangorHousing in 2012 and is one of the 122 elderly or disabled residents who live in the public housing authority’s (PHA’s) properties. Nearly 20 percent of all BangorHousing residents are elderly or disabled, a population disproportionally affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.

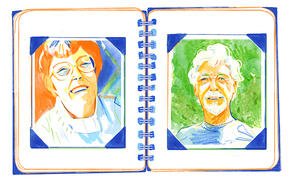

Betty Vandestine, 77, and Ron Reed, 78, are residents of BangorHousing in Bangor, Maine.

Nationwide, more than half (1.13 million) of all households in public housing units are headed by someone 62 or older and/or disabled. People in public housing are more likely to have underlying health conditions that put them at higher risk of contracting COVID-19, and the majority of public housing residents are people of color, whom the pandemic has disproportionately affected and for whom state-sanctioned systemic racism has contributed to lasting housing instability.

In some cities, COVID-19 death rates among people living in public housing, especially seniors, outpace the surrounding areas. In Chicago, more than 80 senior residents in public or subsidized housing died between March 13 and May 10, four times the average during that period for the past five years.

For BangorHousing and other PHAs across the US, the pandemic has meant expanding their role to support older residents’ health, financial and food security, social connection, and housing stability, all while working remotely and protecting their staff members’ health. Services and amenities PHAs normally offer older residents, directly or through partnerships—including meals, communal spaces, and health consultations—all have to be reimagined in a socially distanced environment.

PHAs provide a critical safety net for seniors, but a lack of federal funding has led to approximately $54 billion in unmet repairs in their aging buildings. With even more services needed to help residents during the pandemic, many PHAs must decide between using funds to scale up resident services or to maintain and improve their housing stock.

“[These PHAs are] landlords, and it has been really inspiring in this moment to see how they threw that out the window and said here we are, we're the front line, we’re going to make sure that people are getting help,” said Susan Popkin, director of the Urban Institute’s Housing Opportunities and Services Together Initiative. “They’re finding where the resources are and partnering to bring things in.”

Not every PHA that serves elderly residents has the same resources, nor do they serve the same types of communities. Some PHAs, like Home Forward in Portland, Oregon, have large staffs, funding flexibility, and nearly 2,000 seniors living in a large city, while others, like BangorHousing, have to make do with small staffs, small budgets, and fewer resources in a smaller city. Despite these differences, both PHAs have found ways to respond quickly and meet their elderly residents’ needs during a nationwide crisis.

Relying on partnerships and flexibility

In the early days of social distancing, Home Forward staff leaned on community partnerships for support. The agency was transitioning to a work-from-home environment for the first time, but they still had buildings to sanitize, meals to provide, and residents without phones to check on.

“Early on, we had the indication from some of our partners that they were going to continue their work at those buildings. But as the emergency got to be more and more alarming, some of those providers were no longer able to do that, particularly those that relied heavily on volunteers,” said Monica Foucher, associate director of public relations at Home Forward. “We had to ensure our focus was on core services, so we shifted our approach quickly to fully support direct resource access and vulnerable resident assistance.”

That meant adjusting and expanding cleaning schedules, changing how some senior residents would receive meals, and coordinating regular phone calls with residents. As a large PHA with over 5,000 residents across 46 buildings, some of those shifts in service were easier than others.

“[These PHAs are] landlords, and it has been really inspiring in this moment to see how they threw that out the window and said here we are, we're the front line, we’re going to make sure that people are getting help.”

To continue resident meals, Home Forward started packaging and delivering food directly to residents, rather than having communal meals. One of Home Forward’s partners, Meals on Wheels People, was able to help meet this need, but for over a week, Home Forward pieced together alternative options, including working with local restaurants looking to donate food that would otherwise go to waste. To ensure staff could perform wellness checks on every resident, Home Forward purchased cell phones for the residents of one of their buildings that houses people who had been experiencing homelessness.

Flexible funding, which allows PHAs in the Moving to Work demonstration to combine funds received from the US Department of Housing and Urban Development for capital improvements, voucher programs, and public housing operations to address local needs, has been necessary for Home Forward to provide these resources, according to Evan McAvoy and Melissa Arnold, who supervise Home Forward’s community services team. “It’s allowed us to more easily adapt programming or delivery methods and respond quickly to crisis needs,” they wrote in an email. “We have worked to re-direct partnerships that previously provided in-person and group-based services to providing remote services and delivering physical resources.”

The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act has allowed limited flexible funding for all PHAs, but agencies have not been given clear guidance on how to use that funding. The proposed Health and Economic Recovery Omnibus Emergency Solutions Act, passed by the House in mid-May, includes $4 billion in funding to support tenant-based rental assistance vouchers and $2 billion for public housing operating funds. The Senate has not taken up the bill.

As the pandemic continues, Foucher said Home Forward wants to be able to waive COVID-19-related rent debt that any of their residents, not just seniors who are largely on fixed incomes, might accumulate. If those back rents are waived and additional federal funds are allocated to make up for Home Forward’s losses, the agency could free up funds for services benefiting residents.

Rethinking food delivery

Before the pandemic started spreading in the US, BangorHousing offered a bus to transport its senior residents to the grocery store or Walmart a few times a week so residents without family in the area could buy food and other necessities without worrying about limited mobility. But with the pandemic, having susceptible, elderly residents potentially becoming exposed to the coronavirus in a crowded grocery store was no longer a safe option.

At first, BangorHousing employees tried to go shopping for their residents, said Liz Marsh, director of resident services at BangorHousing. The resident could provide a BangorHousing staff member with their Electronic Benefits Transfer card or debit card and a grocery list, and that staff member would pick up those items.

Betty Vandestine, a 77-year-old resident, took BangorHousing up on that offer because she has trouble wearing face coverings, which made shopping with her daughter difficult. Her daughter’s partner has had health complications, so they were trying to prevent unnecessary exposure.

BangorHousing employee Tommy Lyons delivers a food pantry bag to one of the PHA’s 122 elderly residents.

Although Vandestine liked the service, Marsh said other residents didn’t feel comfortable with the option, and many didn’t use it. So the BangorHousing team decided to make pantry bags to supplement their residents’ regular shopping. To fill the food bags, Marsh started going to grocery stores across Bangor, shopping at Walmart and other big box stores, and ordering food online to be delivered to her house. She includes nonperishables, like pasta sauce and canned vegetables, and necessities like toilet paper. Lately, she’s included some treats as well, so the bags aren’t “just boring food.” Through the program’s 14 weeks, BangorHousing staff delivered 893 bags, with more residents requesting pantry bags each week. The agency ended the program in late June as Maine lifted restrictions, and Bangor staff could begin offering shopping trips for residents again.

With just over 60 percent of BangorHousing’s senior residents requesting food bags, it was a massive, expensive undertaking. Even with a small resident base, the authority’s budget couldn’t provide all the funds necessary to offer quality wraparound services for its senior population. To pay for all the food and other operations, BangorHousing had to turn to grant money. At first, Marsh applied for small grants, hoping that a month’s worth of funding would be enough. But a foundation that funds other BangorHousing programs quickly granted the PHA $20,000 to continue its services during the pandemic.

Reed and Vandestine expressed how much they appreciate the food pantry bags BangorHousing has delivered. Vandestine said that although she doesn’t enjoy the mixed vegetables included in the food delivery bags, she knows if she leaves them in the community room, someone will pick them up to use them. “Anybody can go in there and take what is put in there,” Vandestine said, adding that if anyone leaves fruit or canned beans in the community room, she’ll take those for herself.

Creativity is key for PHAs to continue serving senior residents during a crisis

For seniors, a major benefit of PHA living is the sense of community. Both Home Forward and BangorHousing have community spaces for their seniors, and Home Forward offers communal meals. Because of the pandemic, those services ceased or have been heavily restricted, leaving many senior residents at risk of social-isolation-related health concerns.

BangorHousing and Home Forward have prioritized weekly phone calls with their senior residents to ensure their well-being. BangorHousing’s four staff members have each taken a quarter of the PHA’s 122 senior residents and start making calls every Monday morning. Some calls are quick, but others can last up to 45 minutes, Marsh said, because some residents just really want to talk.

Nason Park Manor, one of BangorHousing’s senior-specific residential buildings

Both BangorHousing and Home Forward are fortunate that their properties have been repaired or refurbished relatively recently, a luxury not all PHAs share. Neither agency has major maintenance or renovation needs, allowing them to shift funding from their capital improvements budgets to cover lost rents and services. PHAs without recent repairs and upgrades will only see those needs increase as they shift funding from maintenance and upgrades toward resident services.

BangorHousing and Home Forward’s quick and creative responses demonstrate that PHAs can find ways to be flexible and continue to ensure services that help their seniors residents during a crisis. Home Forward has relied on its partners in the Portland community, and BangorHousing found grant money to adapt quickly to a challenging situation.

Reed said BangorHousing has taken good care of him over the past couple of months, but the isolation has been hard on him. He visits a couple friends every day while staying socially distanced and has a female friend he has dinner with, but that’s about it for visitors. Otherwise, he tries to stay busy with his jewelry. Reed said that after the pandemic risk subsides, he’s most looking forward to seeing his friends.

“Every day, I [would] go to the local restaurant and drink coffee with some of the old cronies,” Reed said. “You miss everybody lying to one another. The tall tales, you know. That’s about what I miss the most: the socialization of getting together and telling everyone how great you are.”